When Bernard C. Parks, former chief of the Los Angeles Police Department, watched the videotape of Minneapolis officer Derek Chauvin kneeling on George Floyd’s neck, Parks noticed something that most people did not.

As the world well knows, Chauvin and his partners forcibly confronted Floyd outside a convenience store on May 25. With his knee, Chauvin pinned Floyd to the ground. Floyd was face down. He gasped, and he begged Chauvin to let him up. Floyd pleaded: “I can’t breathe.”

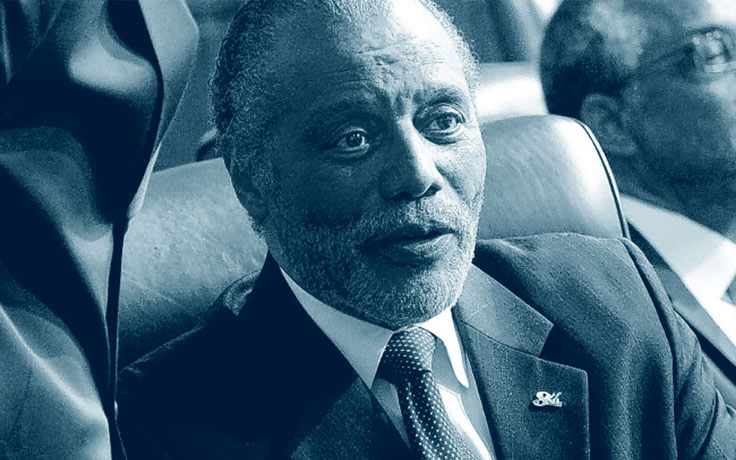

Parks viewed the video with 37 years of experience as a police officer. He is African American and grew up in the LAPD. He became chief in 1997 and was elected to the Los Angeles City Council in 2002. Today, when some people respond to the indisputable observation that “Black lives matter” by insisting that “blue lives matter,” Parks represents both viewpoints — and, as his life is testament, he is willing to air his views and unwilling to bend them to the desires of others. It is not surprising, then, that when Bernard Parks watched Chauvin press his blue knee into Floyd’s black neck, Parks noticed something telling.

“I couldn’t believe that the officer had his hands in his pockets,” Parks said in a recent interview. “When [officers] are talking about how dangerous something is, you can generally tell the real danger in how their partners are reacting and how animated they are. … Here, you’ve gota guy on the ground, and a guy on his neck, and his hands are in his pockets. And his partners are standing there like they’re at a picnic. This is not a dangerous situation.”

Parks had seen something like this before. In 1991, LAPD officers Larry Powell and Tim Wind pulled over Rodney King on a street corner in Lake View Terrace, where King had brought his Hyundai to a stop after evading the Highway Patrol. Ordered from the car, King hesitated and resisted, then attempted to flee. Not realizing that their actions were being captured on videotape — in an era when cellphone cameras had yet to make this an everyday occurrence — Powell and Wind beat King into submission, guided by Sgt. Stacey Koon and assisted by Officer Ted Briseno.

Much has been said and written about the Rodney King beating and the criminal and civil trials that followed. One enduring aspect for Parks was the reaction of others at the scene. A dozen or so officers from various departments — LAPD, Highway Patrol and LAUSD police — watched motionless and did nothing, then or afterward. They were not alarmed; they did not reach for their guns or call for help. From that, Parks said, “You really realized that [King] was not the danger” that Powell and Wind would later claim.

In Minneapolis, Chauvin and his partners conveyed the same calm that Parks remembered from 1991. They took a suspect, pulled him out of his car, forced him to the pavement, cut off his air and then pressed down on him, impassively, until he died. Was that murder?

“It’s as close as you can get,” Parks said.

From the academy to chief

BERNARD PARKS WAS BORN IN BEAUMONT, Texas, in 1943 and was brought as a baby to Los Angeles, where he was raised. He joined the Los Angeles Police Department at age 20 because the prospect of being a police officer paid better than the job he was doing for General Motors. He graduated from the academy and received his badge in 1965.

Parks joined an LAPD that was almost exclusively White, and he finished the academy just in time for the Watts riot, which tore through the city and county and exposed deep fissures in the region’s racial fabric. The McCone Commission, which investigated the riot, heard from witness after witness who complained about police brutality and racism at the LAPD.

Over the next 15 years, Parks studied hard. It was important to do well on written promotional exams, because during the oral exams, senior officers could tell whether the applicant was Black. Parks rose rapidly. White colleagues were alternately impressed and annoyed. One told him he should consider himself a success if he ever made sergeant. In 1980, he made commander — and then deputy chief in two more years. He was a rare black face in the upper echelons of Daryl Gates’ LAPD. Parks had once been regarded as “too young, too Black,” he told me in 2000; but by the time Gates left, Parks was ready.

Gates retired under fire after the King beating and the 1992 rioting that followed the acquittal of officers involved. Parks was among a small number of internal candidates for the chief’s job. But the city and its leadership tired of the LAPD, its history and its struggles. They turned instead to an outsider, Willie L. Williams, the Black police commissioner of Philadelphia.

Williams brought some strengths to Los Angeles. An amiable, easygoing figure with a deft sense for community relations, Williams helped calm the furor around the LAPD. He was popular, at least initially, with the public and political leadership, and his presence allowed some of the pressure on the department to subside.

But Williams never fully grasped the reins of leadership, and his tenure was rocked by his mishandling of allegations that he had accepted freebies from a Las Vegas casino. Questioned about those charges by the Police Commission, he lied. More significantly, the department drifted, unsure about what was expected — should officers be aggressively arresting suspects to drive down crime or improving community relations by focusing on problem solving, even if that meant arrests declined? No one answered those questions convincingly, and when Williams’ five-year term ended, he was asked to leave.

Parks was appointed to succeed him. He served as chief from 1997 to 2002. In many ways, Parks was Williams’ opposite. He was forceful and firmly in control, and the LAPD under his leader- ship focused on crime-fighting. Arrests rose, and crime fell. At the same time, Parks was an aggressive disciplinarian, demoting, reprimanding or firing hundreds of officers. But while Williams was easygoing and friendly, Parks could be combative and bristly, particularly when faced with outside criticism or intervention.

That came to a head with the Rampart police scandal. Corruption and allegations of criminal activity by members of an LAPD CRASH (Community Resources Against Street Hoodlums) unit dated to the Williams years, but they surfaced during Parks’ tenure. And Parks, who could have treated the matter as part of the legacy of his predecessor, instead fought against the revelations and efforts to reform the department to address them.

Most notably, Parks opposed entry of the United States Justice Department into the controversy. This put Parks in the position of seeming to defend the LAPD’s status quo, and it had the odd effect of pitting an African American chief committed to rooting out misconduct against the efforts of outside reformers.

The Justice Department pressed ahead, and the city agreed to enter into a consent decree that ceded authority over many reforms to a federal judge. Parks concluded his term in 2002, and Mayor James Hahn, who had run with strong support among Black voters, made the difficult decision not to reappoint Parks to a second term. The result: Parks had been forced out, and Hahn lost re-election.

Parks then ran for City Council, where he served until 2015. Hahn was appointed to the Superior Court, where he is today. The consent decree, which the city and federal government entered into in 2001, remained in effect until 2013. It is widely credited with providing a structure for reform that Parks’ successor, William Bratton, used to guide the LAPD forward in areas such as training, tracking problem officers and handling complaints.

Combined with previous decrees and department efforts in diversity and community policing, the 2001 decree forms much of the basis for how the LAPD operates today.

Questioning “defunding”

ALL OF WHICH GIVES PARKS an unusually rich history through which to view the current debates over policing, Black Lives Matter, institutional racism and the tension between peaceful protest and civic disorder. He has served as a police officer in communities whose residents all too often have been the victims of aggressive, even racist officers. And he has represented those same communities as a council member, where he has heard their pleas for more protection. Few people have seen questions about race and policing from more sides or with more varied perspectives.

As his comments about Officer Chauvin and George Floyd make clear, Parks is no defender of the cavalier use of force by police. He believes the officers who beat Rodney King were wrong, and that the officers who killed Floyd are guilty of — as he put it — something close to murder.

But he also is suspicious of those who demand “defunding” the police, those who see policing as uniquely susceptible to racism, or those who profess to speak for entire communities or even cities. To take just one example, Parks said he supports increased local investment in services such as mental health and youth programs, both of which might help alleviate crime — and both of which are especially needed in poor communities, like those he represented in council.

But why, he asked, should that money be taken from the police, whose services are needed in these same communities?

“Why it’s police funding I don’t know.

“Why not look at the larger city, county, state budget, and say: ‘These are things we’d like to see funded?’ Why would you pit one agency against your agenda? You’re going to have a flash- back from those who live in certain parts of the city and who say: ‘I’m really not into this. I just want safety.’”

That approach — criticism of police misconduct combined with community sensitivity about safety — makes Parks a lonely voice in the present conversation, a moderate in a debate that does not allow much room for moderation. If this bothers him, he does not let on. He believes this moment demands reflection and a sense of proportion and history, not a sudden reaction.

“Nothing is sustained that does not have a measured approach over time,” he said. “It’s very rare that knee-jerk or sudden flashes sustain. The real issue will be: How far will this go?”

Parks is less even-handed or patient when it comes to critiquing protests and the federal response. He wholeheartedly supports the right to express dissent and opposes the federal government’s clumsy efforts to crack down in places such as Portland, Oregon.

“It’s a major hindrance,” he said of the Trump administration’s use of federal law enforcement agents in protest areas. “No law enforcement officers should be imposed upon [a city] without their request. They’ll never be successful unless there’s coordination.”

Instead, ordering federal law enforcement onto the streets of Portland or Chicago or any other city escalates tension, evades accountability and introduces fear into many communities, he said, especially when those forces include immigration authorities.

Altogether, he said, this makes difficult situations worse.

Why would the federal government send such forces without a request?

“Politics,” he said.

Principled. Or stubborn.

I HAVE KNOWN PARKS for more than 25 years, from before his appointment as chief, through his time in that job, through his council tenure and beyond. We have not always agreed on issues or people. Parks is fiercely critical of some of my former colleagues, and I’ve written critically about some of his friends and allies.

But Parks is nothing if not true to his values and consistent — stubborn, some say — in defense of them.

Years ago, he told me about an incident from the late 1970s, when he was a new captain in the LAPD’s 77th Street Division. Parks hung a picture in his office, a print that a cousin had made portraying a Black woman, her palm resting on her forehead in despair.

Parks was on vacation when a deputy chief, a White man, saw the portrait. The chief pronounced it racially divisive and had it removed.

When he got back from vacation, Parks demanded to know what had happened. He found the print and returned it to his office. It hung in the chief’s office when Parks occupied that space in the old Parker Center, and it hung in his council office after that.

He left the City Council in 2015 and has been retired since. Today, the picture hangs in his house. He won’t be taking it down for anyone.