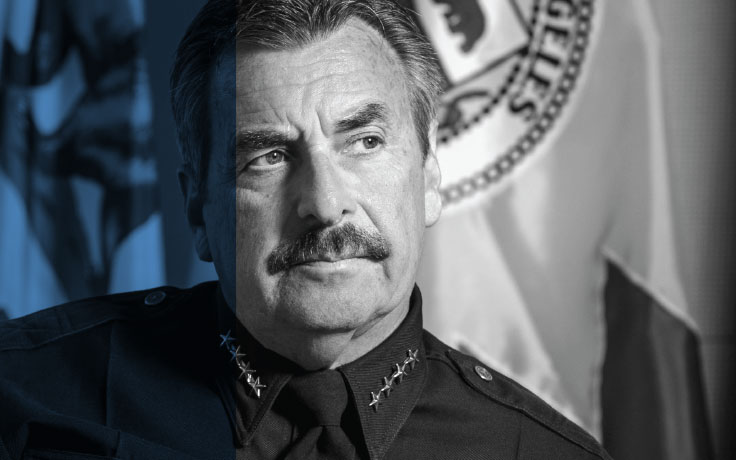

Charlie Beck’s Los Angeles Police Department is a far cry from his father’s. Beck’s dad was a Los Angeles police officer who rose to the rank of deputy chief, and the LAPD of those years was white, fearsome, straight-arrow and distant. Officers were discouraged from interacting with the public for fear it would cause corruption. “Professional policing,” as it was known, was pioneered in Los Angeles. At its best, it offered sturdy protection for an under-policed and growing city. At its worst, it was racist, brutal and alienating.

Today the model is community policing, and the emphases are on nimble analysis of crime data, using it to solve community problems that can cause crime and working with other agencies to keep neighborhoods secure. Police are now encouraged to address blight and quality-of-life offenses, an acknowledgement that the landmark work of James Q. Wilson and his “Broken Windows” theory has made a lasting imprint on the American social and safety landscape.

Police matter

None of that, however, is the most significant change in policing over the past several decades. When Charlie Beck’s dad entered the LAPD, most observers, including academics, police administrators and politicians, assumed that crime was the result of social, racial and economic forces and that the police were supposed to respond. They were there to solve crimes after they happened, not to prevent them. Today, only the most stubborn holdouts cling to that view. It is now almost universally accepted that police officers can affect the commission of crime – that smart policing saves lives, and that police departments can and should be held responsible for the amount of crime being committed in their communities. “We’re not the only factor in determining the presence of crime,” Beck told me recently, “but we’re a very strong factor.”

As the importance of community policing has become clear, however, the difficulty of executing it properly has become even clearer. Indeed, the very techniques that have made policing more effective are now under scrutiny by some skeptics, placing the work of law enforcement in a paradoxical quandary: Departments have made strides against crime and won public trust by focusing on community quality of life, but that same focus has recently stirred anger from critics who complain that departments are engaging in “zero tolerance” and using community policing as an excuse to target minor offenders, sometimes with tragic consequences.

The question for police today is how to act as a constructive force without either abandoning strength some criminals simply need to be subdued or relying too heavily on force and in the process alienating those whose support the police need. Conscientious attention to low-level criminal activity can head off more serious violence, but bullheaded enforcement can alienate and exacerbate tensions. Just ask the police and residents of Ferguson, Mo., or North Charleston, S.C.

This, Los Angeles Police Chief Charlie Beck acknowledges, is a delicate and never-ending struggle. Public support is hard won; if squandered, it is even more difficult to recover.

Growing up in the LAPD

When he was a boy, Charlie Beck could not imagine following his father into the LAPD. Police were viewed with suspicion. He could see how his neighbors treated his father differently. “There’s always the watching and the watched,” he said. “There’s a separation.” Instead, he thought of other things, including motocross racing. (He still has a motocross helmet on a table in his downtown office.) Eventually, however, he was attracted to the responsibility of police work. He joined the LAPD reserves in 1975 and graduated in 1977 as a police officer.

Beck commenced a steady rise through a buffeted and often unstable department. He became a sergeant in 1984, a lieutenant in 1993, a captain in 1999, a commander in 2005 and a deputy chief in 2006. When Chief Bill Bratton resigned in 2009, Mayor Antonio Villaraigosa picked Beck to succeed him.

As chief, Charlie Beck has fused the reform instincts of Bratton with his own deep knowledge of the Police Department, including his first-hand observation of some of its lowest moments. Beck was a promising sergeant in the early 1990s when the LAPD hit bottom: Some of its officers, caught on videotape, Tasered, beat and kicked Rodney G. King, a robbery parolee they had pulled over after a high-speed chase. King was African American, and the beating caused a public outcry. When a Ventura County jury acquitted three of the officers and a mistrial was declared for the fourth, Los Angeles erupted into a riot that killed more than 50 people, injured thousands and caused damage estimated as high as $1 billion. Moreover, Beck saw the tragic consequences of bitter silence between then-Mayor Tom Bradley, a former LAPD officer himself, and Daryl F. Gates, police chief at the time, who resigned under criticism that his officers were slow to respond to the riot.

Easygoing and self-deprecating, Beck is sometimes underestimated. But he’s whip-smart and a shrewd observer of City Hall. He has served under two very different mayors, the energetic Villaraigosa and the more cerebral Eric Garcetti, and has forged good working relationships with both.

Beck’s tenure has not been without incident. He was criticized last year for approving the Police Department’s purchase of his daughter’s horse for an equestrian unit, after saying he had no role in the transaction. In addition, the Los Angeles Times has analyzed the department’s crime data and concluded some of its numbers are inaccurate. At the same time, some categories of crime have increased after years of decline. But the difference between now and the early 1990s is stark: Back then, more than 1,000 people were being slain by others every year; last year 260 people were murdered in Los Angeles.

Technology and data

Today’s LAPD is different. It is more diverse and more oriented toward the people it polices than was the department that lost the public’s trust in the early 1990s.

It is also more proficient technically. Patrol officers are equipped with mobile computers and in-car video cameras. Some wear body cameras, intended to reassure the public that police conduct is being monitored and to reassure officers that they will have evidence against false complaints. At the same time, commercial security cameras are becoming ubiquitous, and the LAPD is looking for ways to tap into their images. Drones may become part of the LAPD’s arsenal, although civil libertarians and other activists are trying to head that off, or at least impose rules that will limit their use. Meanwhile, advances in forensics have revolutionized detective work while also, Beck warns, raising “false expectations” that every criminal case comes neatly wrapped in conclusive DNA evidence.

Most important, modern policing at the LAPD has plumbed data in ways that would have baffled chiefs a generation ago. This aspect of the LAPD’s work, however, is much misunderstood. Yes, crime trends are important, and a city is better off with fewer people killed or raped or robbed. But news stories tend to report the bottom line whether crime is up or down while the real value of data is not so much raw numbers as how those numbers are used to forge strategies. “It isn’t about data itself,” Beck said. “It’s how you use it.”

For the LAPD, strategizing from data happens during a weekly meeting at headquarters. During one recent session, leaders of a San Fernando Valley division presented statistics showing an uptick in petty thefts. On the surface, that didn’t mean much. Maybe children were out of school and lifting candy bars, or maybe gangs were targeting stores to line their pockets scenarios that would warrant radically different responses. But petty thefts, left unchecked, make a community feel vulnerable and lawless, precisely the conditions that “Broken Windows” suggests might give rise to crimes that are more serious.

So commanders dug in, demanding to know what was causing the uptick. The answer: Retail chains, such as WalMart, averse to chasing off customers, were resisting measures that might make it harder to grab items and instead addressing the problem by nabbing shoplifters after the fact, an approach that might be better for business but that encourages crime to flourish. The response in this case: working with those stores to improve security not just for the sake of the stores but also of their surrounding neighborhoods.

The focus on lower-level crime can make community relations more difficult. Those stopped for shoplifting or illegal vending or selling small amounts of drugs can feel rousted and harassed. Surely, they ask, don’t the police in a city the size of Los Angeles have better things to do? That is especially true when those being arrested for small offenses are members of minority groups who feel targeted by a department with a history of racial insensitivity.

Beck acknowledges this fallout but says that allowing small crimes to foster an attitude of lawlessness also has implications for minority groups. As we talked, he reached for the LAPD’s 2014 Homicide Report. He showed me a chart on page 15. Of the 260 people slain in Los Angeles last year, 231 were black or Latino; just 18 were white. Most of those killed lived in poor neighborhoods, and a majority of the killings were gang-related.

“Your demographic,” Beck said to me, a 52-year-old white male, “is almost immune from violent crime.”

That helps explain why a smaller percentage of murders has been cleared in recent years (gang crimes are notoriously difficult to solve because witnesses are reluctant to come forward). It also explains why the murders of white people are more likely to be solved than those of blacks or Latinos (whites are more likely to be killed by an acquaintance or “loved” one).

It also underscores the dilemma that now confronts the LAPD and other modern police departments: The same police work that angers minority communities is often what protects them.

The reminders of that quandary flare up over and over again. Earlier this spring, LAPD officers received a report that a Skid Row man had been assaulted and robbed. Responding, they tried to take a suspect, later identified as Charly “Africa” Leundeu Keunang, into custody. Keunang was a bank robber with a history of mental illness, and he resisted. There was a struggle, and police shot and killed him. An episode that began with an attempt to protect one homeless man ended instead with another homeless man dead. Like so many incidents these days, it was captured on video, and public anger flared again.

It was one more reminder of the shifting responsibility of police in a modern age.

The challenge of Beck’s father’s generation was to maintain order. The challenge for Beck’s immediate predecessors was to regain trust. The challenge for Beck is to use the tools of science and community policing to thwart crime without overusing them to squander that support.

“The job of building community trust,” Beck said, “is never finished.”