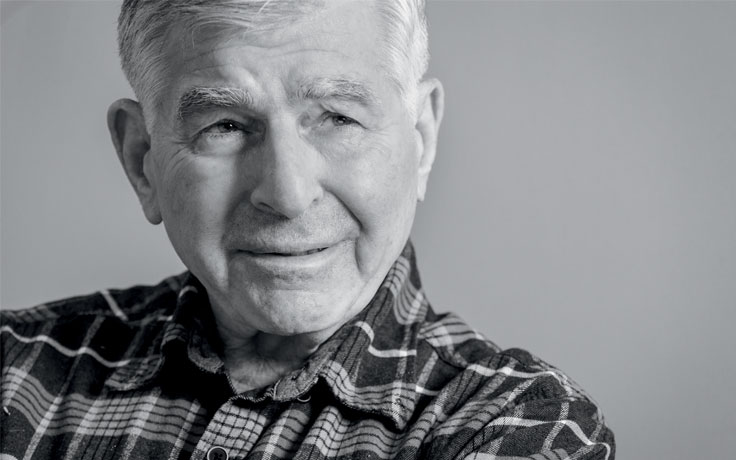

MICHAEL DUKAKIS TALKS WITH THE ENERGY AND PRECISION that I remember from our first encounter 43 years ago, when he was governor of Massachusetts. At the time, I was working on a story for the Los Angeles Times about a new generation of governors like Dukakis and Jerry Brown, who were trying to shed the New Deal orthodoxy of the Democratic Party. Today, Dukakis is still questioning orthodoxy, now from the classroom.

We met recently in his office at the UCLA Luskin School of Public Affairs, where he teaches half the year. He spends the other half at Northeastern University in Boston. Dukakis is now, as he was then, a fit, diminutive man. He was dressed in a button-down sport shirt and khaki pants. He has an engaging, lively manner, well suited for this generation of students and their short attention spans.

Nothing about him suggests retirement, old age or a retreat from the busy world. “How old are you?” he asked me. “I’m 83,” I replied. “I’ve got a year on you,” he said. “I’m 84 and still at it.” Observing me taking notes and recording him, he said something that revealed a lot about his outlook on life: “How are you enjoying it?” he asked. “Keep at it. What you’re doing makes life a hell of a lot more interesting than sitting around.”

He teaches two courses at UCLA. “One is an undergraduate course, which I co-teach with Dan Mitchell,” he said. “Been doing it for 21 years. He’s a labor economist, and it’s called California Policy Issues, which is a lot of

fun. We have 60 students, divide them in half. It’s pretty intense. It’s a very popular course, and we cover the whole range of issues affecting California, which are the issues affecting the country.”

Campus politics — then and now

“Interesting” is a word that doesn’t do justice to our times. On campuses around the country, students are demonstrating for gun control and for young immigrants threatened with deportation. It brings back memories of when California was a leading incubator of the anti-Vietnam War movement.

“Remember Vietnam?” Dukakis said. “You and I were young in those days. What happened? We got into that damn war, it wasn’t going well, we lost 55,000 Americans and God knows how many Vietnamese on both sides. It was the young people who finally started the process of getting us out of there.”

Activists were considered on the fringe when they first opposed the war. Democratic leaders supported our invasion of Vietnam. But young people rallied behind the antiwar candidate, Sen. Eugene McCarthy, an austere, somewhat remote figure, who was an unlikely magnet for rebellious youth. The press and the party establishment dismissed McCarthy and his young supporters. But their campaign laid the groundwork for political opposition to the war, although the conflict lasted for six more painful years.

Does Dukakis see a parallel? Yes, he does. Because of the Florida shootings, he said, young people “are mad as hell, and they ought to be. Kids at school have become regular targets of shooters all over America, and I hope we’re going to see, coming out of this, the same kind of youth-driven leadership that we got during Vietnam. It was the young people who basically shut that war down. And I hope they are going to do the same in this case. And they have a perfect right to do so because they are the targets — they and their teachers. This isn’t some far-off mythical story here. Kids are getting killed, and their teachers who were supposed to shield them.

“Will this kind of awaken the conscience of the country? Will it be young people who drive this debate? I think so. I hope so. We’ll see. But I don’t think it’s just more of the same. I don’t think these young people are willing to accept this.”

President Donald Trump, Dukakis said, is “a threat to democracy. He doesn’t understand it. He doesn’t understand what democracy means. He doesn’t understand the role you guys [the media] play in this, the importance of having a vigorous, open, free press that can inform us of what is going on. He seems to resent this. This fake news thing. Where did that come from? What’s he talking about?”

The 1988 presidential campaign

Dukakis has experienced politics from the Massachusetts legislature to the governor’s office to his loss in the presidential campaign of 1988 against George H.W. Bush. Although polls had Dukakis ahead at the beginning of the campaign, he fell victim to a savage attack orchestrated by a Republican dirty tricks pioneer, the late Lee Atwater, who blasted Dukakis with two television ads that doomed him. The most devastating was the infamous Willie Horton ad, featuring a black Massachusetts inmate, Willie Horton, who raped a white woman while on a state prison weekend pass. The other featured Dukakis in an unfortunate campaign stunt, driving a tank to convince voters he was as hawkish as Bush. His dress shirt, visible under military attire, combined with his short stature, didn’t add up to the image of a tank driver. Atwater got the footage and ran with it.

Dukakis, after losing, returned to his governor’s job, finished his term, quit politics and became a college professor. He is deeply involved in teaching public policy. On his classroom agenda are efforts by state and local governments in liberal states like California, Massachusetts and New York to pursue progressive policies in the face of the Trump administration, which is trying to stifle them. Dukakis is finding a receptive audience.

“In a sense, Trump has got these kids hopped up for public service,” he said. “They don’t like him. They have been really energized. Kids come into my office every day asking, ‘How can I get into this? What can I do? How did you get started?’ Lots of them, both here and on the other coast. And I spend a lot of time working with them, trying to see if I can be helpful in terms of a career path, and we push them hard on internships, that kind of thing, and they are very serious about this.

“Fabulous young people are coming out of here, and they want to do public work. They are excited about it. They are committed to it. It helps to have folks around who can kind of open doors for them. I spend a lot of time making phone calls to people. If I had my druthers, every kid in America takes civics. We don’t teach civics. And they would do an internship with a local official.”

Dukakis starts his students thinking about what stimulating times these are and how challenging they are for politicians, particularly those in liberal cities and states.

He and his students discuss federalism — power-sharing between Washington and the states — an issue exemplified by California’s resistance to Trump. Dukakis talks about the power of city and state governments to influence policies such as controlling global warming. He cites the work of former New York mayor Michael Bloomberg and his Bloomberg Philanthropies, whose philosophy is that Americans cannot rely on national governments or international bodies to solve global warming, and that change must start at the local level.

“Now, given what is going on in Washington, you’ve got this interesting development in which states like California and others get help from Mike Bloomberg,” Dukakis said. “He and his foundation are basically proceeding to develop a set of policies nationally and internationally, which are obviously very different than the ones coming out of the White House, and you’ve got the governor of California meeting the president of China to talk about the Paris treaty.”

The separation of federal and state power has been a defining American issue since the beginning. But Dukakis feels the issue has now changed. “In these days, it’s quite scrambled,” he said. “Traditionally conservatives have been states’ righters, right? So we now have a situation where a very conservative bare majority in the House wants to prevent my state from enforcing the toughest gun laws in the country — which, by the way, have produced the lowest homicide rate in the country — which is a strange way to go about supporting states’ rights. If states don’t have the ability to protect themselves from people who are running around with concealed handguns, for that matter automatic weapons, what kind of states’ right is that?” The states, he said, have “a fundamental police power, the ability to protect your own citizens, and we’re now being told that violates some kind of overriding federal priority.”

Dukakis recommended listening to police officers when they say they can do a better job of keeping communities safe than citizens can who are armed with guns. “It is pretty obvious it’s got nothing to do with states’ rights,” he said. “It never was about states’ rights. It was about ideology.”

And racism?

“I think the guy who is currently attorney general, Jeff Sessions, believes that immigration laws should be enforced and ignoring their violation is a disservice to law enforcement, the rule of law and that kind of thing. But he is not going after states that make it very difficult for people of color or poor people to vote. So what’s this all about? There’s no principle here, it seems to me. Is there a racist element to all of this? Of course there is.”

A public life

A compelling part of the Dukakis story is his openness about his wife Kitty’s fight against depression and how she has been helped by electroconvulsive therapy. The treatment involves brief electrical stimulation of the brain while a person is under anesthesia. “Some are helped by drugs,” Dukakis told me. “Kitty is one [who was] never helped by antidepressants.” But electroconvulsive therapy worked. “This treatment literally saved her life,” he said. Now she has ECT maintenance treatments every six weeks or so, either at Massachusetts General Hospital or at UCLA. And she devotes much of her time to counseling those with depression and explaining ECT treatment. She speaks at events, hosts support groups at their home and has written a book: Shock: The Healing Power of Electroconvulsive Therapy.

“There must be thousands she has helped,” Dukakis said. “People will pick up the phone and talk to her. I’m very proud of her.”

When my visit to his office ended, Dukakis put on his stylish — but not L.A. skinny — brown leather jacket, picked up his briefcase and headed across campus on a busy schedule, a man still on a mission after all these years.