WHEN THE FILING PERIOD TO run for mayor of Los Angeles opened in March 2020, not even Nostradamus could have predicted that, two years later, the runoff would pit U.S. Rep. Karen Bass against developer Rick Caruso. The reason was simple: Neither at the time seemed outwardly interested in succeeding a termed-out Eric Garcetti.

Bass’ profile was soaring after she chaired the Congressional Black Caucus and then made the shortlist to be Joe Biden’s running mate. She was a shoo-in for her seat as long as she wanted it, and some speculated she could succeed Speaker Nancy Pelosi. Caruso, meanwhile, was a billionaire with a real estate empire highlighted by the Grove and the Americana at Brand, places that transformed how Angelenos gather. His eponymous company was planning projects across Southern California.

Why would either give up such success for the havoc of a bitter campaign, one where losing was a possibility, and winning might be worse? The next mayor will lead a city of 4 million people struggling to emerge from the pandemic, while facing worsening crime and a stubbornly persistent homelessness crisis.

So why risk it all? Start with a thirst for power and a commitment to this city’s civic health, though the blend of ambition and generosity is different in the two candidates. Whatever their differences, Caruso and Bass both think that he or she alone is the best person to lead this city, with all its glories and troubles.

Much has been made of the pair’s personal and professional dissimilarities: Bass is an African American woman, a lifelong Democrat who came from a modest background and climbed the political ladder; her path is one of growth from the ground up. Caruso is a white, devoutly Catholic male, born into privilege and the owner of a $100 million yacht, a former Republican who registered as a Democrat only in January. Relationships with the civic elite, from City Hall to USC, where he chaired the board of trustees, helped set the stage for his candidacy. In a city where voters often complain about a lack of choice, the differences are stark. Not since businessman Richard Riordan beat Councilman Mike Woo 29 years ago has Los Angeles seen such a chasm between mayoral finalists.

At the same time, the fact that both Bass and Caruso chucked an easy future, and vanquished a field of City Hall politicians in the June election, suggests some similarities as well.

To understand these two contenders, it makes sense to look not just two years back but rather 30 or 40. For it’s with the time machine view that one realizes both Bass and Caruso have spent decades in the grinding business of Los Angeles civic life.

Bass grew up in the Venice-Fairfax neighborhood, the child of a mailman and a hair salon owner who became a stay-at-home mom. Bass protested the Vietnam War while in high school, and she began her career as a physician’s assistant. A job in the L.A. County+USC Medical Center emergency room exposed her to the ravages of crack cocaine in South Los Angeles, and in 1990 she launched the Community Coalition for Substance Abuse Prevention and Treatment. Running a social justice nonprofit that worked to help Black and Latino communities generated few headlines, but it was the epitome of street-level work, one with clear lines to the homelessness crisis of today. When I spoke with Bass for Los Angeles magazine after she announced her candidacy last October, she said running for mayor was a chance to bring her career back to where it started. “Full circle is the absolute theme,” she told me. “Because I feel like we’re facing a life-and-death crisis again.”

Caruso grew up a few miles and a whole world away, in the Trousdale Estates section of Beverly Hills, the son of Dollar Rent A Car founder Hank Caruso. He attended Harvard Prep (now Harvard Westlake), matriculated to USC and earned a law degree from Pepperdine. He began working in real estate full-time in 1987.

As his fortune grew, Caruso, too, displayed a civic side; Mayor Tom Bradley appointed him to the board overseeing the Department of Water and Power when he was just 25, and within two years he was the panel’s president. Another mayor, James Hahn, named him to the Los Angeles Police Commission, where he served two years as president. Neither position paid a dime, and both required countless hours every week, not to mention often tangling with lobbyists and politicians, and taking flack from angry members of the public.

For Caruso and many other civic-minded Angelenos, Los Angeles’ system of commission leadership offers a different entry point into politics than the route followed by Bass. The system, a product of the city’s Progressive-era charter, is intended to tap public-minded citizens and bring them to the work of leadership. It was created as a counterweight to populism, and it works to infuse government with private expertise while also reinforcing the role of elites in fashioning and overseeing policy. It is, in short, a system for people like Caruso, who thrived under it.

The avalanche of political ads on which Caruso has spent tens of millions of dollars of his fortune is the most obvious difference in their mayoral campaigns, but there are others. Bass, particularly since finishing first in the June election, has appeared at a steady stream of events where she glad-hands and works to curry favor with key voter blocs. Likable and warm, Bass appreciates the appreciation given her at these events. She builds from an ability to connect and charm.

Caruso also seeks these blocs, though he approaches them more as a businessman. He tends to keep a tight leash on proceedings, and projects himself less as affable neighbor than as a cool-eyed CEO. He favors one-on-one interviews with TV reporters and holds campaign events at places such as the Grove, where his team has a better chance of keeping out expletive-spewing disrupters.

It’s cliché to say that family is key to both, but that doesn’t mean it’s not true. And the two have endured challenges. Caruso’s daughter was born with hearing loss, leading to hearing aids and extensive speech therapy. Decades before, his father was indicted by federal authorities on charges related to his auto empire. Hank Caruso pleaded guilty to multiple counts, though the plea was later set aside and the charges dismissed. Caruso rarely mentions his father, and that history has not been widely discussed during the campaign.

In 2006, two years after Bass won a seat in the California Assembly, she suffered a life-altering family tragedy: Her 23-year-old daughter, Emilia, and Emilia’s husband, Michael Wright, were killed in a car crash on the 405 freeway. “It changes you forever, that’s for sure,” Bass said in a 2020 interview with OZY Media founder Carlos Watson. “My daughter and son-in-law were the center of my life.”

Bass added that the memory of her daughter also pushed her forward. “She would have been very upset with me if I didn’t carry on,” Bass told Watson. Indeed, her career arc continued; in 2008 she became assembly speaker, the first Black woman to hold the post. Two years later she was elected to Congress.

Caruso has three sons and a daughter; Bass four stepchildren and two grandchildren. Their families are occasionally glimpsed on the campaign trail. Toward the end of a debate at USC in March, when the moderator surprised Caruso by asking about TV habits, he called to his wife in the crowd. “Tina, what was the last thing we binged?” he asked. “Help me here.”

Bass’ 7-year-old grandson, Henry, appeared with his mother, Yvette Lechuga, at a Latinos con Karen Bass event in Boyle Heights in April.

“She’s an amazing mother, an amazing grandmother,” Lechuga said from the Mariachi Plaza stage. Bass beamed lovingly at the boy wearing a gray suit and a wide-brimmed hat. When Bass referred to Henry and another grandchild, she intoned, “They know I’m the grandmom who spoils them.”

Bass was shaky in some early campaign appearances, perhaps the result of not having had a contested election in more than a decade. At a December forum hosted by the Stonewall Democratic Club, and a press conference to unveil her homelessness plan the next month, she spoke at warp speed, and seemed unable to connect with the audience. She has since found her footing, and now uniformly appears comfortable, informed and experienced. At campaign happenings she builds on the enthusiasm of adoring crowds. She dresses impeccably.

Caruso also displays sartorial splendor. At campaign events he speaks confidently and persuasively, skills honed over decades of community meetings for his mega-developments. A 2007 Los Angeles magazine article referred to him “attending hundreds of get-togethers and coffee klatches” as he pushed a project in Arcadia.

Yet Caruso relishes combat, too. I saw him throw darts at the political establishment during a 2011 speech downtown when he was previously considering running for mayor. “I strongly believe that City Hall is a roadblock that’s keeping Los Angeles from reaching its potential,” he said. When the topic of trying to land an NFL team in the city came up, he sniffed that some council members “have a tough time spelling the word football.”

That tendency was on display again at the USC debate. When City Attorney Mike Feuer challenged Caruso on building affordable housing, Caruso started to answer, then veered with a barbed, “Mike, I’m sorry that you opened this door,” and mentioned a federal raid on Feuer’s office. The raid had nothing to do with affordable housing, and while attacking an opponent is part of any debate, Caruso’s aside showed his combative side — a gratuitous swipe at an opponent to take him down a notch.

As election day approaches, Bass and Caruso have claimed their turf; Bass boasts of her experience, relationships and knowledge of communities too often overlooked, as well as her ties to the White House and the dividends her Washington connections may pay for Los Angeles. Caruso describes a city that is, if not yet in collapse, at least headed that way. He doles out a prescription of confronting homelessness, crime and City Hall corruption, and charges that “career politicians” have failed L.A.

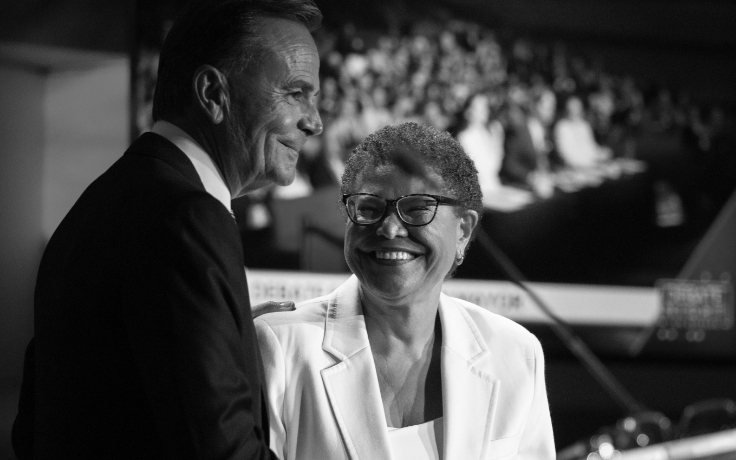

But even as they lean on their differences, hints of their shared experience surface. When he hit the “career politicians” theme at the USC debate, Bass bristled. She said, “You know, Rick, you’re my friend.”

Caruso agreed. “We are friends,” he said.

Bass made the point as a roundabout way of chiding Caruso for denigrating public service and those who give their lives to it. But the acknowledgment of friendship hung in the air.

The connection between Bass and Caruso is hardly close or personal. They have come to this election from vastly different experiences and values. And yet, the mention of friendship was a recognition of their common ambition and work — the painstaking labor of leadership, whether by election or appointment, to improve communities or hold agencies accountable; and the shared sense that each is the right person to guide this city forward. There is much that separates Caruso and Bass, but they have that in common.