Anthony Rendon does not tweet.

“I don’t know how to,” says the speaker of the California State Assembly. “I have never sent a tweet in my life. Staff does the tweeting for me.”

Indeed, Rendon thinks tweeting is “an experiment that failed. . . . The conversations we have [on Twitter] are significantly dumbed down.” He might be old-school, but he is not dumbed down.

Rendon met me on a recent Saturday for a conversation at one of his favorite places, Horchateria Rio Luna, a coffee shop at a mall in Paramount, the blue-collar and largely-Latino city he represents in Southeast Los Angeles County. Shoppers were heading toward a bargain food market and an auto supply store. Nobody was wearing a tie.

Except Rendon. It accented his blue suit and white shirt. But he doesn’t have to impress people; they understand him. Rendon is Latino. He was raised in his Assembly district, and like many of his constituents, he comes from a working-class home. He started out in warehouses, on the overnight shift.

“What you see is what you get,” said his cousin, Ed Rendon, who as a union official, helped launch him into politics. “He’s the same Anthony who played football in the back yard.”

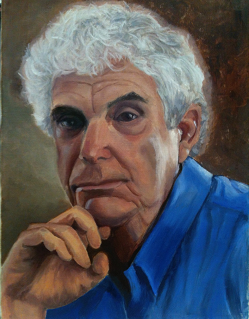

The speaker is 51 and, he conceded to me, strictly old-school. He talks softly, in a thoughtful manner that would have been suitable for the academic life he once considered, instead of the political career he chose. “He’s a quiet, reserved person, ” said Assembly Majority Leader Ian Calderon of Whittier, one of his allies.

My conversation with Rendon came at a turning point for the state, the legislature and his career. We ranged across topics that included the roots of his power, his relations with other Assembly members, the impact that the Assembly will have on the state – and his reluctant adjustment to fast-paced social media. We also talked about his life story.

In the legislature, Rendon shares the spotlight with Toni Atkins, the Senate president pro tem. Even more attention will be on Gavin Newsom, the new governor. All are Democrats, as are the majority of Assembly members and state senators. But because of tradition and history, mainly the legacy of two powerful predecessors, Jesse Unruh and Willie Brown, the speakership has a special resonance. In addition to inheriting the Unruh and Brown mantles, Rendon appoints all of the Assembly’s committee chairs and, importantly, decides the amount of their administrative funding, the size of their staffs and their office space. It adds up to clout.

Newsom’s state of the state message made it clear that he has a strong agenda of his own, an agenda different from that of his predecessor, Gov. Jerry Brown, who served eight years. Unlike Brown, Newsom faces a legislature newly empowered by the voters’ decision to extend Assembly and Senate term limits from six years to 12. Expect some power to shift from the new governor to the more experienced legislature. Experience and smarts count in the Capitol.

If Rendon keeps winning re-election, he could remain speaker until 2024, longer than anyone since Willie Brown, who held the position from 1980 to 1995. The extension of term limits also means that Atkins could hold onto her post for just as long.

I asked Rendon how this would work.

“Extension of term limits has changed everything,” he said.

He recalled how Assemblyman Mike Eng moved from one chairmanship to another in his term-limited six years in the Assembly. “In the six years he was in the legislature, he chaired banking for two, transportation for two and business and professions for two, never getting the chance to immerse himself in a subject,” Rendon said. “I think it is impossible to become an expert in any policy area in those short stints.”

He compared Eng’s tenure to that anticipated by Assemblyman Jose Medina, who chairs the higher education committee. “When we’re all done, Jose Medina may be higher education chair for 11 years,” Rendon said. “He’ll be an expert. He’ll know the inside and outside of the master plan [for higher education]. He’ll know what has been tried, what hasn’t. Being around for 12 years empowers members, and not just vis a vis the third house – the lobbyists – but also with staff. There is more institutional memory.”

“In the last five years, it has been the biggest change we’ve had in California politics, and I think it’s been great.”

From Cerritos to MOCA

Rendon’s journey to prominence began after high school – on a bus.

It took him home after his all-night jobs in warehouses, where he unloaded trucks. That was his reward – or punishment – for a .83 high school grade point average. “The rocking of the bus would put me to sleep, ” he said, and he would wake up when the bus stopped. One of its stops was in front of Cypress College, where he watched students head for class.

He decided to become one of them. ” “I had a sister who was at Whittier College. She put books on my desk.”

Subtle persuasion, or not so subtle?

“Subtle,” he said. “One was The Brothers Karamazov.”

He enrolled at Cerritos College.

What was his goal?

“I don’t know. I was just trying to get off the bus.

“But I took a course in philosophy. I loved it, loved it, loved it. It seemed like the professor was asking enduring questions. It seems the questions are more relevant now than ever. What is justice? It’s a very relevant question.” The experience changed his life. “For a couple of years, when I was working the graveyard shift, I was sleepwalking, literally and figuratively. When you ask yourself very fundamental questions, I think it evokes a sense of immediacy. It makes it impossible not to think about things. It’s still that way for me.”

From Cerritos College, Rendon went to California State University, Fullerton. “More than anything I had a good liberal arts education,” he said. “I learned about classical music. I learned about literature. I took a course in geography. It was very life broadening.”

Rendon got a bachelor’s degree and a master’s degree at Fullerton, received a National Endowment for the Humanities fellowship and earned a Ph.D. in political science from UC Riverside. He did post-doctoral work at Boston University, then became executive director of Plaza de la Raza Child Development Services, interim director of the California League of Conservation Voters and chief operating officer of the Mexican American Opportunity Foundation.

“I worked at MOCA,” he said, “and I got very interested in art – and in architecture, especially.”

But his work in non-profits had attracted him to politics. In 2012, he ran for the Assembly and was elected. He became speaker in 2017.

A History of Speakers

Rendon is quite different from Willie Brown and Jesse Unruh in the 1960s, who were all-powerful.

“My wife is working on a doctorate in education,” he said, “and she was reading a story about Unruh, all the methods he used to centralize power. When I was reflecting on it, I almost felt as though I have done the opposite of everything he did. I have very much tried to decentralize power. I realize that in being a long-term speaker, there’s implicitly a lot of power inherent in that. But I try to farm out as much power as I possibly can to committee chairs.

“People still don’t believe it. Lobbyists will come to me and ask me to do this and that, and I ask them if they have talked to the committee chairs, and they think I’m winking and nodding at them.”

As he shifted power to committee chairs, he reduced the size of his office. “I eliminated 25 to 30 staff members.”

While Brown and Unruh prided themselves on their authorship of major legislation, “I haven’t introduced a bill since I have become speaker.”

Why?

“Speakers tend to take all of the oxygen out of the room,” he said. “A lot of legislative leaders try to get their hands on every big policy area. It puts a target on the bill itself. The other house and other members know that something is in your bill and try to hold it hostage legislatively and leverage it for something they want.”

Instead, he lets committee chairs introduce legislation, whether it is for something local, like improving the Los Angeles River, or for something of major statewide importance, such as the minimum wage.

On one notable occasion, he earned his colleagues’ gratitude by keeping a controversial bill away from the committees. It was legislation, passed by the Senate, which would have created a state system of Medicare for all, or single-payer health care. Although the bill was backed by the tough and influential California Nurses Association, Rendon killed it by never permitting a hearing.

He said the bill was expensive and did not provide for funding, a deficiency overlooked by Senate backers who had rushed it through. In the Assembly, the nurses and others demanded public hearings. This might have whipped up support, but it also would have forced committee members to vote for or against a bill that had little or no chance of passing. “They had intimidated a lot of members of the Senate,” Rendon said. ” I thought it was an absolute trap.”

Rendon held the bill.

To take the heat off members?

“Yeah,” he replied. “That was the point. All the venom was directed toward me, and that’s okay.”

Proponents of the bill tried to mount a recall against Rendon, but it went nowhere.

Assemblyman Calderon told me that Rendon’s move showed two sources of his power. First, Calderon said, it illustrated Rendon’s concern for other members. “He takes the tough shots,” Calderon said. Second, Rendon’s battle over the single-payer bill showed how deeply he burrows into complex legislation. “He has substance,” Calderon said, “the capacity to do the work.”

Communicating in a new era

In the social-media age, with events moving ever faster, is substance enough? Can Rendon, with his deliberative style, keep up?

An example is the Capitol’s sexual harassment scandal. For as long as I can remember, lawmakers had been pressuring staff and lobbyists for sex. It was part of the Capitol culture, although it was unspoken. Then the #MeToo Movement made the harassment public. A lobbyist, Adama Iwu, wrote a letter condemning it. More than 140 women signed the letter, including Rendon’s wife, Annie.

Reporter Melanie Mason broke the story in the Los Angeles Times, and the issue exploded. When “we published the story,” said John Myers, the Times‘ Sacramento bureau chief, “we could see all the social media light up within seconds.” There was “immediate feedback on whether they (the legislature) had done enough yet. Some said they should have done more.”

Rendon reacted with calmness uncommon in the social media world.

“We had established a committee on sexual harassment before that letter,” he told me. “I remember my wife being asked to sign the letter. I’m glad she signed.” He told KQED that his wife had helped educate him. “Whereas I think I was focused on policy and procedures, she helped bring those to life by telling me real stories that real people had experienced.”

I followed Rendon from Horchateria to the El Hussein Community Center in Bell, a gathering place for the Lebanese community. The atmosphere was grassroots, as old-school as the speaker himself. Rendon’s staff had assembled 26 volunteer lawyers who were offering free advice on matters including employment law, workers compensation, health care and immigration.

Rendon was in no hurry. He stood at the back of the room, watching and talking quietly to an aide.

Issues discussed by these voters, or potential voters, would find their way from Bell to Sacramento. There, Rendon would learn if this service for his constituents and his quiet, collaborative manner – so unlike Unruh’s and Willie Brown’s – was working in the hyper-active age of Twitter.