Los Angeles voters have approved measures raising many millions of dollars for construction of housing for the homeless living on the streets of the Los Angeles area. Yet their numbers grow, and little has been done to provide them shelter.

Weary of the vague and bureaucratic explanations of elected politicians and other officials, I dove into the details of a single project, Los Angeles city parking lot 731, located at Pacific Avenue and Venice Boulevard.

Nonprofit housing organizations Venice Community Housing, led by respected homeless housing advocate Becky Dennison, and Hollywood Community Housing Corp. have been selected to develop 140 housing units on the public lot, with parking spaces to replace those lost to the new apartments. Nonprofits build many such projects, assembling packages of public and private funds. The Los Angeles Times has powerfully called attention to homelessness, and housing enjoys broad public support.

Why, then, is the property still a parking lot? The answers are complicated, and they explain why the bond measure and a 2017 countywide sales tax increase, intended to raise $350 million a year, have not translated into housing for those made homeless by mental and physical illness, drug and alcohol use, family breakups and, to an increasing extent, high rent and a shortage of affordable housing.

It takes more than two years of hearings, negotiations, red tape and construction to complete such a project. By then, many of the women and men now on the streets will be dead. “Victims of natural disasters are not left to sleep on our streets, but refugees from economic hardship, gentrification, a housing shortage, domestic violence, sexual abuse, addiction and mental illness are left to fend for themselves in the elements,” said Los Angeles City Councilman Mike Bonin, who is trying to win approval for the parking lot project. “That is unacceptable and intolerable.”

Homelessness in Los Angeles County has increased by 23% since the money-raising measures were approved. Today, almost 60,000 people are living on the streets of the county. In the city of Los Angeles, homelessness is up 20 percent; 34,000 people are without residences. But just 615 apartments for the homeless and other poor people are in various stages of planning, with most of them not scheduled for completion until 2019 or 2020.

The Venice parking lot seems ideal for a city-sponsored affordable apartment project. At 121,000 square feet, it’s one of the city’s biggest parking lots, large enough for 188 vehicles. The city owns the land so no lengthy condemnation proceedings or haggling over price is needed. But Councilman Bonin, who represents the area, has struggled to get the project off the ground. In a report to constituents, he related this tangled story:

Venice Community Housing held more than 30 “ listening sessions” to win over reluctant neighbors, without much success. The Venice Neighborhood Council, generally suspicious of low-cost housing for the homeless, represents the neighbors and will weigh in on the project. Venice property owners are already campaigning against it.

After the neighborhood council comes a hearing before a high-ranking city planning department official, the zoning administrator. If she or he favors it, the city council planning committee is the next stop, followed by the full city council and Mayor Eric Garcetti. They must also vote on an environmental impact report. Because of the project’s proximity to the beach, the Coastal Commission probably will also have to consider the project. Two more city departments will have a say in the allocation of funds.

Other homeless projects are sponsored by the county. These require permissions from two separate county departments involved in the issue.

Supposedly overseeing this bureaucratic nightmare, but with no real power to issue orders, is the Los Angeles Homeless Services Authority, a combination of city and county officials. The authority, which also approves funding for housing organizations, is in charge of finding prospective tenants. This is done through a process so cumbersome that it seems likea cruel joke on the people for whom the housing is intended.

Field workers are dispatched to areas where the homeless can be found. The workers, strangers to their target audience, ask the homeless more than 80 questions, many of them highly personal. Those considered most in need are put at the head of a list — only to then wait up to two years for a place to live.

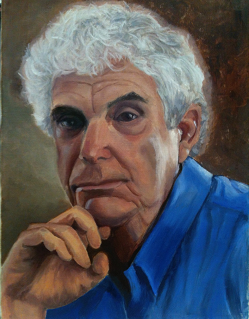

“It is a bureaucracy to end all bureaucracies,” said Zev Yaroslavsky who, in two terms as a county supervisor, became the leading expert and advocate for homeless housing.

“There is no silver bullet to solve this problem,” said Yaroslavsky, now teaching at UCLA’s Luskin School of Public Affairs. But he added, “There ought to be a sense of urgency in getting something built.”

Many solutions have been offered. Rooms in half-vacant rundown motels could be leased, as envisioned in a pending Los Angeles ordinance. Temporary living spaces with tents or small wood dwellings with bathrooms and showers could be put up on city- and county-owned spaces. Churches and synagogues could be persuaded to open their parking lots at night to those living in vehicles. Owners of private property could be paid by the city or county to build small houses for the homeless in their back yards.

In the end, it’s up to Mayor Garcetti. He has said he favors legislation to ease state environmental impact report requirements. But he must do more. He must meet face to face with NIMBY homeowners and overly cautious public officials and get them to agree to build affordable housing

throughout the city.

Garcetti should visit every encampment and bring do-nothing officials with him. He should ditch the meetings and memos. Bang heads. Be tough, aggressive and inspirational. My advice to the mayor? See the film “Darkest Hour,” and channel Winston Churchill. In the meantime, Lot 731 remains vacant.