THE IMPACT OF COVID-19 on American public education has been devastating. Classes conducted via Zoom caused learning loss for many students. Children suddenly devoid of peer interaction endured mental health challenges and an erosion of social skills. Teachers who had long provided extra attention to struggling kids were left frustrated at the far end of an Internet connection.

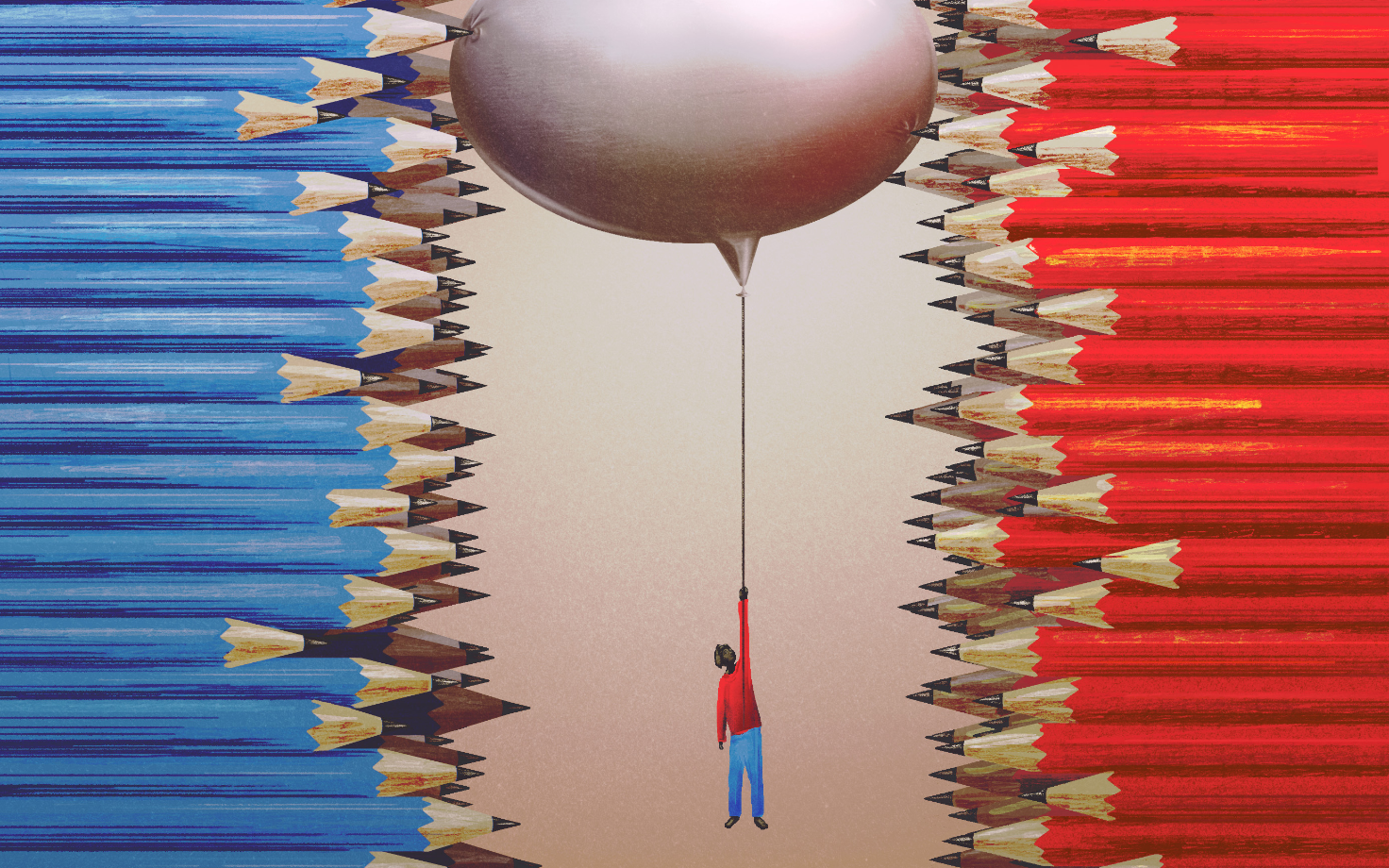

Classes are back in session, but schools across the country have encountered another insidious effect of the pandemic — a staggering rise in intolerance and hatred, particularly around issues of race and LGBTQ+ acceptance. A national political divide has bled from cable news programs and social media down into public high school classrooms, with the most impactful effects in politically divided “purple” communities, according to a recent report published by UCLA and UC Riverside researchers.

The education system has never operated in a blissful vacuum, of course, and teenagers have forever been directing mean-spirited invective at classmates.

But the rhetoric has recently intensified, and the development of critical thinking skills crucial to the high school experience is being undermined in an atmosphere where misinformation is growing and the window for honest discussion and debate is narrowing.

Los Angeles and beyond

“Critical thinking means exploring issues without fear, exploring issues that sometimes are difficult to explore,” said Austin Beutner, a former superintendent of the Los Angeles Unified School District. “When political forces make that harder in schools, they are harming kids, or harming the nature of education they get.”

The issue is spelled out in “Educating for a Diverse Democracy: The Chilling Role of Political Conflict in Blue, Purple, and Red Communities.” The 49-page report, published in November, was written by John Rogers, a UCLA professor and director of the university’s Institute for Democracy, Education and Access, and Joseph Kahne, a professor of education and co-director of the Civic Engagement Research Group at UC Riverside.

As with so many segments of society, the state of American education was battered by the COVID-19 pandemic, whose effect on learning in public schools was deep and wide. In November, the California Department of Education released test scores that had dropped across the board in English and math. Students in low-income households were hit especially hard. Declines were attributed to economic hardships caused by parents contracting COVID, losing jobs, or dying. Technology challenges made distance learning even more difficult.

LAUSD schools confronted all of those issues and more. Despite an ambitious program to give every student an Internet device and reliable service, test scores showed that a preponderance of them failed to meet grade-level standards for either English or math. Scores in those areas dropped to their lowest levels in five years even as teachers handed out higher grades.

Elsewhere in the nation, culture wars added to the challenge. Florida Gov. Ron DeSantis and Virginia Gov. Glenn Youngkin were among officials who sought to rein in what could be taught in schools. Partisan-driven disagreements about curriculum and parent involvement became a norm.

All of this served to compound the already difficult challenge of teaching kids.

Trump, division, COVID-19

“Educating for a Diverse Democracy” builds from a basic premise: People from different backgrounds and beliefs need to work together, and that starts at an early age, often in school. This dovetails with a central purpose of public education, which is “to strengthen our democracy by preparing students for informed civil engagement with civic and political life.”

This has been hampered, the report finds, by a divisive political atmosphere under former President Donald Trump, and by disagreements about pandemic restrictions, such as mask and vaccine mandates. These differences are exacerbated, the report notes, by the efforts of small but well-organized conservative groups adept at weaponizing topics such as Critical Race Theory — even if that is something rarely addressed in high school.

The findings are based on a survey of 682 public high school principals across the country, with nearly three dozen follow-up interviews. The researchers divided respondents into three segments: Blue territories for congressional districts where less than 45% of voters supported Trump in 2020; Red for where the Trump vote was 55% or greater; and Purple for everywhere else.

The results reveal growing division. The report found that 45% of principals saw “more” or “much more” conflict during the 2021-2022 school year than before the pandemic. The geographic divide came into play when principals were asked about derogatory remarks students made to liberal or conservative classmates: 19% of school leaders in Blue territories and 20% in Red areas said this happened multiple times. The figure was 32% in Purple communities.

Then there is race. The report found that 48% of all principals said parents or community members attempted to limit teaching about issues of race and racism — but this figure was 63% in Purple communities.

Another disturbing finding: 22% of principals in both Red and Blue communities reported multiple occasions in which students made hostile or demeaning remarks about LGBTQ+ classmates. In Purple districts, it was 32%.

The divisions in schools are real, and their impact goes even further, said Dr. Manuel Ponce, a clinical associate professor and director of Loyola Marymount University’s Institute of School Leadership and Administration. Ponce, who is helping develop the next generation of school administrators, said the discord worries his candidates.

“They are seeing the rhetoric … and the disintegration of public discourse,” said Ponce, who formerly worked as a principal and regional superintendent with the Los Angeles area charter school group PUC Schools. “Our leaders come to us concerned about how they will navigate the world we are living in.”

The role of misinformation

Another troubling element detailed in “Educating for a Diverse Democracy” is the spread of misinformation. Right-leaning groups not only reject the reporting of mainstream media but actively campaign against it. The report said 64% of all principals had parents or community members challenge the information or media sources used by teachers. Again, there was a geographic disparity: In 2022, 22% of Blue area and 16% of Red area principals reported parent or community challenges three or more times. The rate was 35% in Purple districts.

One principal quoted in the report described how parents “regularly send him articles” from sources such as the websites of conspiracist Alex Jones or Fox News host Tucker Carlson. The principal told the researchers, “[The parents] think they’re right … and everyone else is wrong.”

An important aspect of “Educating for a Diverse Democracy” is that it builds on past work. Rogers, who has long researched ways to promote an egalitarian system in public schools, conducted a study in 2018 — two years into Trump’s term — on what principals were experiencing. At the time, he found a changing political climate, with school leaders reporting that some students were emboldened and operating with less sensitivity than before.

Then came COVID shutdowns and restrictions, and a nation further divided by the November 2020 elections. Political machinations intensified. In the fall of 2020 and spring of 2021, Rogers noted, conservative activists increasingly focused attention on public schools. This took multiple forms: protests over what was taught; vocal and vitriolic complaints at formerly sleepy school board meetings; even right-wing candidates seeking school board seats.

Rogers’ 2018 report became a baseline. He and Kahne were able to chronicle how cracks seen before the pandemic widened into chasms. Consider the statistic of 32% of principals in 2022 reporting multiple hostile or demeaning remarks about LGBTQ+ students: In 2018, the figure had been 10%.

So too with the 35% of principals who in 2022 reported three or more challenges of the media sources used by teachers: Four years before, the rate was 12%.

This shows that public schools can both reflect nationwide tensions — and become battlegrounds.

“The shift that I’ve seen play out from 2018 to 2022,” Rogers said, “is an environment in which the broad political rhetoric seeping into public schools has given way to political campaigns that are purposely targeting public schools and using culturally divisive issues as the centerpiece of those attacks.”

The chilling effect on teachers

The harm comes not only from what is said aloud but also from what is not said later. “Educating for a Diverse Democracy” reveals that conflicts — even from a small minority of parents or of the community — can have a “chilling effect.” Some teachers and principals become unwilling to revisit certain topics for fear of stoking tensions.

“There are lots of angry parents or community members who come to school board meetings or who post on websites,” Rogers said, “and that creates a climate in which educators up and down the system are wary of leaning into lessons about race, or leaning into efforts to protect and celebrate queer students.

“The chilling effect in part comes out of this sense of confusion about what are we now allowed to do, and what are we now prohibited from doing? It also comes out of this climate of fear in which there is threatening rhetoric and sometimes physical threats that are playing out in the public realm [and] that lead educators to worry about their jobs, or lead them to worry about what is going to happen to their person.”

Rogers and Kahne posit that there are ways to combat this trend. Their report makes repeated references to a loud minority of parents and activists, leaving a silent majority who, if activated, could unify and be a force.

Additionally, there are opportunities to give more support and professional development to teachers. Further, their report finds that principals who themselves are civically engaged tend to lead schools that seek to educate for a “diverse democracy.”

There are other options, as well, although they can require leaders to gird for battle. When asked what suggestions he would have for principals and superintendents, Beutner, the former L.A. Unified superintendent, said: “Their true north is what’s right for the kid and what works

in the classroom. If they need to stand in front of the crazies, or between the crazies, sometimes it comes with the job. That’s what I would be doing. I think that’s what many of them are trying to do.”

Ponce, the director of LMU’s Institute of School Leadership and Administration, suggested that schools and districts recommit to their core mission and vision. Knowing precisely what one stands for, he said, can be a roadmap in the face of intolerance.

“Can you draw a line from what you say in your mission and vision to something connected to the community, connected to the needs

of the students and parents, connected to clear equity, and ensure that you are looking at finding ways to fill equity gaps?” he asked. “There has to first be a clear understanding of what that anchor is going to be. Then that becomes non-negotiable in schools.”

Rogers stressed the importance of schools engaging with their entire constituencies — teachers, district leaders, community members, even students. Civic engagement requires active and open participation.

“For too long we’ve seen educators use a set of practices … where they were basically telling students and parents what to do,” he said. “There need to be modes of outreach and engagement where educators are really inviting parents and students to work with them.”

His message: To combat hatred and intolerance, it takes not a village but the entire educational community.