The Westwood/Rancho Park Metro station in West Los Angeles is nestled snugly in a development of single-family homes that date from the 1950s. The location is something of a head scratcher. On a recent Friday morning, only a few people exited the westbound train, and not very many boarded the next train going east. The only high-rises in sight housed commercial offices along Pico Boulevard to the north. There was nothing to suggest multi-family residential opportunities.

Not long ago, UCLA Professor Paavo Monkkonen stood at the Westwood/Rancho Park station talking to members of a production crew from NPR’s podcast “Planet Money.” He had asked them to meet him there because it offers an excellent example of one of the problems of urban planning in California: Despite a crisis in affordable housing, there seems to be little political will to change zoning laws to build multi-residential housing units. At the same time, it seems politically acceptable to build an expensive mass transit system with rail stations in areas with little mass to transport.

To Monkkonen, this speaks to the elephant in the room in public planning: The single-family home. That bias is particularly noticeable in Los Angeles, where 75% of the residential land area is zoned for low-density, single-family houses and stems from a time when the ideal of a good family, household and neighborhood was, in many ways, exclusionary.

Questioning the single-family home

The impact is profound and far-reaching. Single-family zoning covers half the population of the city. Zoning restrictions in Westside communities have a trickle-down effect in Boyle Heights. The lack of new or affordable housing keeps residents from moving up the economic ladder. Twenty-five years ago, those with the financial means might move from areas where they were renting or perhaps where they owned in comparatively modest surroundings to higher-end areas near better schools, transportation, or the beach. That kind of urban/suburban migration in the Los Angeles Basin is less common now as housing supplies have shrunk and the cost of existing homes has become prohibitive. So residents stay in what were once euphemistically called “starter communities” instead of moving to other parts of the city and making way for new families.

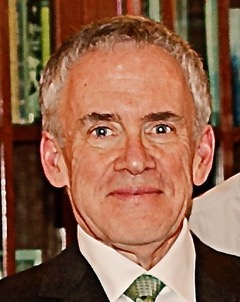

Monkkonen is an associate professor of urban planning and public policy at the UCLA Luskin School of Public Affairs and vice chair of the Department of Urban Planning. He researches the ways policies and markets shape urban development and social segregation not only in California but in cities around the world. He says that he has been increasingly vocal about local planning issues related to housing—not only in op-eds about funding affordable housing, but in writing letters to officials about state bills and local plans and ordinances. In a November, 2016, research paper, “Understanding and Challenging the Opposition to Housing Construction in California’s Urban Areas,” he offers reasons for and some modest ways to mitigate the affordable housing crisis. Another paper, co-authored with UCLA professor Michael C. Lens, on whether strict land use regulations increase income segregation in metropolitan areas, was published in the December, 2015, issue of the Journal of the American Planning Association. Their findings were included in the White House’s “Housing Development Toolkit” as part of an effort by the Obama Administration to address the issue of housing supply in major metropolitan markets.

Opposition to zoning changes in areas developed for single-family homes can be based on factors including an historic desire for sprawling, horizontal homes on large parcels of land and concerns about traffic, noise and pollution. To a degree, the opposition also can be mounted in support of economic segregation that keeps those with lesser means out of the community. Add to that a somewhat irrational disregard for land developers and a knee-jerk reaction that equates multi-family residences to high-rise, glass and steel buildings, and you have a formula that generally maintains the status quo. Single-family homeowners are, as Monkkonen has noted, something of a cartel because their interests—centered around increasing the price of their homes on the market—hold sway with elected officials. Generally speaking, single-family homeowners have the time and money to fight efforts to change zoning laws. Homeowners are more active than renters on election day and more active in neighborhood councils and representative boards.

But single-family zoning and high home prices may also hurt the regional economy by limiting population growth, which can influence the job market by discouraging highly skilled workers from coming and cause companies to leave. Those costs, Monkkonen notes, were also among the reasons for Toyota’s decision to move from Torrance to Texas in 2014.

Low-density zoning can also have a negative environmental impact. It forces cities to expand horizontally, which increases consumption of land and creates longer commutes, which in turn generate more greenhouse gases. Interestingly, environmental concerns are often used as a pretext in blocking developments for reasons that have little to do with the environment. The California Environmental Quality Act, Monkkonen writes, has been cited effectively to block or reduce the size of developments. One Los Angeles city planner, he says, has noticed that most of the lawsuits filed under this act have been in opposition to residential, not commercial, projects.

L.A. outgrows original vision

Monkkonen, 40, was born in Los Angeles, grew up in Culver City and went to UC Berkeley where he studied classical civilizations as an undergraduate. After earning his bachelor’s degree, he taught English in Mexico and then Spain before working for a time in San Francisco with a non-profit group that helped people with developmental disabilities in public housing. He went on to get his master’s in public policy at UCLA and his Ph.D. in City and Regional Planning at Berkeley. Before returning to UCLA to teach, he spent three years as an assistant professor of urban planning at the University of Hong Kong.

In an hour-long interview in his spare and tidy office on the fifth floor of the Luskin School, Monkkonen spoke quietly and thoughtfully about the social impacts of housing planning policy. He wore a polo shirt, jeans and sneakers. More than once the conversation turned to Culver City, where his family came to live from Minnesota in 1977 so his father could take a teaching position in the history department at UCLA. His father would go on to be among the first faculty members in the Department of Public Policy. His mother, a former librarian at UCLA and then at an elementary school, still lives in the home where he was raised. Monkkonen and his wife, who works in the collection management department at the Los Angeles County Museum of Art, now live in Culver City (regrettably, also in a single-family home, he said), and their six-year old daughter goes to the same Spanish immersion elementary school that he attended as a child.

Being back in the city of his youth, he said, has given him a close look at change and status quo in Southern California. Monkkonen said many of his former classmates from Culver City, while successful, can’t afford to buy houses there. Many of their parents, however, are still in their old family homes. Some won’t – or can’t – leave because of the property tax hit that they might take under Proposition 13 by selling and moving into something more to scale for their current lives, such as a townhouse.

Much of the urban planning in the Los Angeles area, Monkkonen said, was done when the population was only about 5 million. Now, it is 18 million, but zoning, generally speaking, hasn’t changed to reflect that reality. Although the state is in a housing crisis, he said, the policy changes needed to ease it would include some that have little public support, such as reforming the mortgage income deduction on federal taxes, the government’s largest housing subsidy, which, he writes, “promotes the use of housing as an investment and in turn incentivizes homeowners to rationally oppose any changes that negatively impact the value of their homes.”

Property taxes under Proposition 13 also shape land use policy by shielding homeowners from what Monkkonen describes as “the fiscal consequences of increased home values.” In addition, he writes, the complex approval process for new construction “has become a central moment for land value recapture, and new construction is asked to shoulder the burden of funding infrastructure, affordable housing, and other community benefits, while existing structures (and residents) face no such obligation. This has a restrictive impact on development, making projects with large profit margins the only ones feasible.”

At the other end of the spectrum, he notes, rent control or rent stabilization laws, while shielding residents from current market prices for housing, may have the “unintended consequences of creating a constituency that is more concerned with tenant protections than widespread affordability.”

In his view, land-use issues are too important to be left entirely to cities, and it has become increasingly important for regional or state authorities to help regulate zoning. Currently, California requires cities to produce housing units to show they can meet regional housing need allocations, he said, but the requirement “carries no financial carrots or sticks for actual production of housing.”

Recommendations for change

Monkkonen has several recommendations:

- Enforce and enhance existing housing laws.

- Modify the project approval process to include input from a wider cross-section of residents, including renters.

- Encourage government agencies to proactively produce data and literature to assist growing efforts by pro-housing advocates to inform the public debate.

When asked if any major cities in California are doing a good job with housing planning, Monkkonen was hard-pressed to name even one. He said Seattle, Portland and Minneapolis had recently made headway in creating multi-family housing.

The key in Los Angeles and other parts of California, he said, is educating the public about what changes in zoning laws actually mean and offering examples where zoning changes have enhanced neighborhoods. He said a four-story model of housing that he sees in other cities might be an answer, and he doesn’t understand the antipathy toward such a solution.

“If you’ve traveled and lived in places where there are mid-rise density neighborhoods all over the world, they are often fabulous and look nice, and kids are playing there, and everything,” he said. “They’re socially just as great as any single-family neighborhood in L.A.”

Monkkonen said he sees his generation as the one beginning the work to dismantle the legacy of single-family zoning and create a new mentality about cities for California. That would include changing the narrative in urban planning from one that simply keeps most of the city the way it has been to one that that is more inclusive and “would continuously adapt the built environment throughout the city for all its residents.”