JORJA LEAP’S SMALL UCLA OFFICE IS A CAMPUS OASIS. The anthropologist turned gang researcher has replaced standard-issue university furniture with a modern wooden desk, a couch and a muted rug. The room is orderly, the papers on her desk tidy. One wall features large, striking black-and-white photos of Jane Goodall, Mahatma Gandhi and John Lennon, among others — an homage to activists who have inspired her. But the serenity is deceiving.

Ask Professor Leap about trauma and violence prevention, and — even 25 years into her work — she bounces noticeably in her chair, her hands moving constantly. She talks so fast it is hard to take notes. She has been hanging out with gang members in L.A.’s toughest neighborhoods since the early 1990s, showing up at the scenes of homicides at 2 a.m., consoling family members, getting to know young people on the streets and trying to understand how to help them leave gang life behind.

She has done much of her research with fellow professor Todd Franke at the Luskin School of Public Affairs. They have gained international recognition for their analyses of crisis intervention, violence prevention and the social impact of trauma. A key to their success, Leap said during an interview in the stillness of her office, far from the savagery that she studies, is attracting philanthropic dollars “in a robust and involved way.” Franke agreed. Large charitable foundations, as well as individual philanthropists, are “often willing to fund things that public funding won’t” he said. Finding money to study crossover youths — those who move among schools, child welfare and the courts — is especially difficult, he said. But some foundations have been eager partners.

With support from the John Randolph Haynes and Dora Haynes Foundation and the California Wellness Foundation, as well as from Los Angeles County, Leap and Franke have focused on Los Angeles-based Homeboy Industries, trying to determine why some gang members become successful contributors to society, while others stay trapped in a spiral of violence and revenge. Founded in 1988 by Father Gregory Boyle, a Jesuit priest whose photo hangs on Leap’s wall, Homeboy operates on the premise that jobs, education and social services will do more than incarceration to improve the lives of former gang members and their communities.

Homeboy employs hundreds of former gang members in its business enterprises. It offers a wide range of services, including mental health counseling, job training, tattoo removal, legal assistance, anger management and parenting classes. Leap and Franke have tracked 300 Homeboy alums since 2008. They have found that while two out of three people incarcerated in California return to prison, only one in three of those who have participated in Homeboy programs re-offend and land back behind bars. Homeboy’s expansive wrap-around services, Leap and Franke said, are a vital part of this success.

“What our research shows,” Leap said, “is that Homeboy has created a therapeutic community through its emphasis on the relational” — forcing former gang rivals to work side by side and talk. “You can’t hate someone you sit across the table from,” she said. The relationships that gang members build with former gang members, mentors, social welfare professionals, counselors and educators are essential, she said, to improving their physical, social and mental well-being — and to improving their communities.

Hard-earned experience in gangs

Jorja Leap, 61, is a second-generation Angeleno. Her experience with gangs is hard-earned. It began in 1978, when she became a social worker in Watts caring for abused children. She watched, devastated, as some gravitated into gangs. After earning a doctorate in anthropology from UCLA, she moved into research and conflict resolution, working with Balkan Wars victims in Bosnia and Kosovo, as well as with families who lost loved ones in the 9/11 terrorist attacks. Focusing her research on violence prevention became an abiding passion.

Todd Franke, 62, is trained in social work and educational psychology. Since joining UCLA in 1992, he has explored the impact of disability and chronic illness on school-age children and researched how adolescents solve social problems, how to better integrate health and social services in school settings, and how urban mobility impacts children’s education and their social development.

The two have a long history of collaboration. In addition to the Homeboy research, Franke and Leap led an evaluation of a California Community Foundation-funded initiative in South Los Angeles designed to help young African American men develop the skills to complete high school and move on to post-secondary educational opportunities. Leap and Franke have received funding from the Children’s Institute Inc. to examine its Project Fatherhood Program, based at 10 sites throughout Southern California. The program helps absentee fathers connect with their children, play a meaningful role in their lives and, by doing that, improve the long-term social health of their communities.

Improving wellbeing, defined in this broad way, is the mission, as well, of the California Wellness Foundation. Created by Health Net, it opened its doors in the anguished aftermath of the 1992 Los Angeles riots. The foundation now awards between $30 million and $40 million annually statewide. “We were trying to figure out solutions to violence at a time when not many folks were looking at this issue,” said Julio Marcial, until recently a program director at Cal Wellness, who worked closely with Leap and Franke.

“Taking on violence was not necessarily our idea,” Marcial said. “It was the mothers and fathers, the ER physicians who saw too many young men coming in with gunshots, and folks in academia who said, ‘Please take this issue on.’”

Involving young people and family members as active participants in research had “not been tried quite like this before,” Marcial said. “We didn’t know what to expect.” Marcial credits a variety of public and privately funded programs and research initiatives, like the Homeboy project, with creating “a synergy of people and organizations.” That synergy has helped decrease gun violence among young people across California by 50 to 60 percent between 1992 and 2015, he said, citing data from the California Public Health Department.

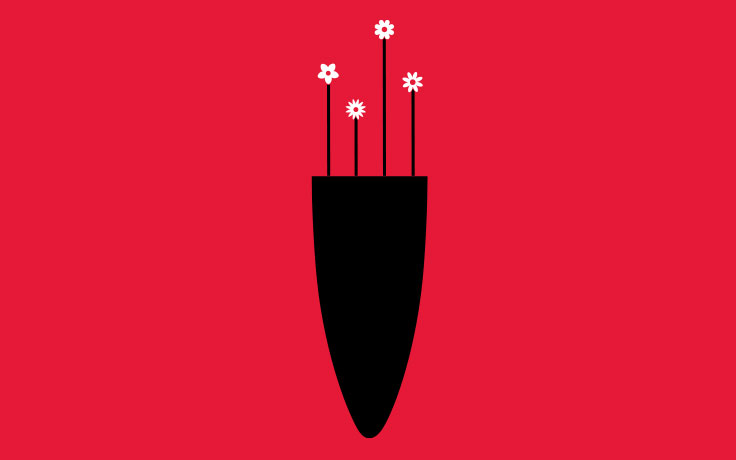

Last year, Cal Wellness helped create a new fund, Hope and Heal, to support proven solutions, as well as what executive director Brian Malte calls “big bets” to address the “gun violence epidemic.” Malte had spent 20 years with the Brady Campaign to Prevent Gun Violence, whose name honors White House press secretary Jim Brady, who was gravely wounded in 1981 during an attempt to assassinate President Reagan. Hope and Heal made its first grants late this spring, after what Malte describes as his “listening tour” across California to determine priorities. “We’re not going to push for new legislation,” he said. “We have the luxury of having strong gun laws in California.” Instead, Hope and Heal will invest in research, advocacy and on-the-ground programs that can reach the root causes of violent crime, suicide and domestic violence.

Malte points to Sacramento and Richmond as models. By deploying community members known as violence interrupters, who are trained to defuse potentially deadly encounters, both cities have reduced gun homicides. Stockton is trying a similar program. “We want to change the narrative about gun violence,” Malte said. “The current narrative is that it’s hopeless, there aren’t solutions; it’s hyper-politicized, based on mass shootings, which drive coverage and legislation.” But violence interruption, along with other efforts, he said, indeed offers hope.

Hope and Heal’s main financial sponsor is the New Venture Fund in Washington, D.C., which oversees a variety of donor-driven projects. Hope and Heal also has received support from Cal Wellness, the California Endowment, the Blue Cross of California Foundation, the Akonadi Foundation and other philanthropies. Malte began with $1.5 million. He now has commitments for another $600,000 and proposals for more.

The power of philanthropy, and its limits

For Malte, Franke and Leap, private foundations and individual philanthropists have generally proven to be adventurous and flexible partners. But there are potential problems with accepting private money, as there are with public grants. Funding always comes with “strings attached,” Leap said, so she asks herself, “Are they strings I can live with? Do they want research findings, or do they want me to take dictation?

“I’ve found my way to work with institutions that want to be a partner,” she said. Her goal is to create a partnership based on “equality rather than control.” Still, she says, her major worry remains “autonomy, autonomy, autonomy.”

Another concern, Franke said, is renewing grants. “Foundations are willing to fund you once, maybe twice,” he said, but securing ongoing funding can be challenging. Nonetheless, he said, the challenge can be positive, because it creates “opportunities for more individuals and groups and for new ways of looking at the same problems.”

Evaluating projects when they are completed can raise still other concerns. Not all funders will support evaluations — and if they do, being truthful about what worked during the research and what didn’t work requires delicacy. Sometimes, Franke said, donors “don’t want to know that they spent all this money, and it didn’t work.

“What I promise them is to find out what parts are working and what parts aren’t — and to come up with recommendations, if they want them, about the parts that aren’t.”

Wealthy individuals as well as foundations also can pressure researchers to pursue pet projects — or validate pet peeves — regardless of evidence. That’s why Malte, who is responsible for both raising funds and helping to award grants, relies on a steering committee of representatives from among Hope and Heal’s major funders.

By far, most donors participate in positive ways, Leap said. She recently received a gift from Los Angeles psychiatrist William Resnick, who said he simply wanted to be involved in her work. “He’s very thoughtful, very intentional,” she said, and he is now helping design a Luskin-based training program aimed at assisting people to become more effective nonprofit board members.

In action, in Watts

Jorja Leap is stepping up her involvement in Watts. She has become the co-founder, along with Luskin alum Karrah Lompa, of the Watts Leadership Institute. With support from the Annenberg Foundation and Cal Wellness, among others, the institute, which opened early last year, is fostering nonprofit entrepreneurs in South Los Angeles.

It was born of a 2013 Luskin report that cited a need among small, struggling agencies in Watts for local leaders with skills in fundraising, policy advocacy and communication technology — skills that will make it possible for them to compete successfully for philanthropic dollars. The institute pairs participants with coach-mentors from UCLA. Initial participants will mentor others to build a new generation of nonprofit leaders.

To Leap, this “represents the best kind of partnership between UCLA and philanthropy.”