TWO IMPRESSIONS LINGER FROM THESE conversations with Los Angeles Mayor Karen Bass. One was her openness. There is a refreshing curiosity about Bass, a break from mayors who came to office professing to know the solutions to the city’s problems, only to learn that they did not. By contrast, Bass readily acknowledged that she is learning as she goes about the pressing, urgent work of housing this city’s vast population of homeless people.

The other was a small moment. In describing the struggles to get government agencies and housing developers not to require proof of a homeless person’s poverty, Bass remarked that “they can’t accept my people because they have to prove income.” Note the “my people.”

It’s hard to imagine Richard Riordan or even Tom Bradley thinking of the poorest residents of this city as “my people.” They were serious, important and in many ways generous leaders, but they led from above. Not Bass. Her small comment revealed much about how she sees her service and how it springs from her conscience.

Just over a year into her tenure, Bass has yet to produce dramatic reductions in the number of unhoused people in this city. Her Inside Safe program has helped liberate thousands of people from encampments, but it has not created a reliable path from there to permanent housing. The temporary solution, placing those people in motels, is shockingly expensive, as Bass herself acknowledged.

As time goes on, the pressure on Bass to produce tangible results grows more intense; so, too, does her determination.

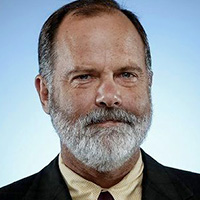

Blueprint editor Jim Newton interviewed Bass on two occasions for this Table Talk, in December 2023 and March 2024. This transcript draws from those interviews, splicing together the two conversations, both of which took place in Bass’ City Hall office.

BLUEPRINT: How do you measure your progress on this issue? Is it how many people remain homeless? Or how many people have you gotten off the street? How do you define success or failure?

KAREN BASS: I think probably the greatest success was disproving the myth that people don’t want to leave the streets. What that tells me is that there’s a way out of this, that this is solvable.

The greatest challenge is the scale. … The greatest thing I learned [last] year are the pieces that need to happen to put this together.

Getting thousands of people off the street is the greatest success. Figuring out what the pathway forward should be, what the pieces should be … is the greatest challenge.

BP: Are there pieces that are harder than you expected?

KB: Yes! Getting people out of interim and into permanent [housing]. And all of the barriers, even when there’s housing available.

It’s been like peeling an onion. And you cry when you peel an onion.

Every peel, I find a barrier, and then I have to go chase down that barrier. But it’s not hard to knock the barriers down. And some of the barriers are because, “Well, this is the way we’ve always done it.”

And some of the barriers are, for instance, “You have to prove your income [to get a benefit].” And, “You need a government-issued ID.”

“But I’m in a tent. What’s my address? Don’t you think I’m poor enough?”

So every time I peel back, then I go off in pursuit of that barrier, and we’ve been able to move the barriers. But every time we move a barrier, we find out that somebody else has that same barrier.

For example, the barrier on income and IDs. We peeled that back. We got HUD [the federal Department of Housing and Urban Development] to waive it … to agree to presumptive eligibility.

Then we found out that the developers might have the same barrier. They have to income-prove. The men and women who are building the housing, they can’t accept my people because they have to prove income. So then we’re in pursuit of that barrier.

But those are solvable.

BP: There’s new inputs into this pipeline all the time, whether it’s evictions or or Texas Gov. Greg Greg Abbott sending immigrants from the border or any number of things. Given that, are you worried that the numbers may not yet be coming down?

KB: I am. That’s another peel of the onion. I repurposed the Mayor’s Fund to focus on [evictions]. Eric [Garcetti, Bass’ predecessor as mayor] used it for COVID, brilliantly. … We are regranting that money to smaller, community-based, grassroots organizations to focus on the ZIP codes where the eviction rates are the highest. … There’s a lot of evictions on pretty high-income ZIP codes. We’re not focusing our efforts there. Just because they’re evicted does not mean they’re going to be homeless. … Those people will be OK.

But if you go to the lowest income ZIP codes with high numbers of evictions and knock on doors and go to schools and all that, they won’t be OK. And we have recruited an army of pro bono attorneys to represent people. And at the same time, we’ve also tried to pay attention to the landlords, especially small landlords. So when you hear about rental assistance, that goes to the landlord, not to the tenant.

We have no program to prevent homelessness. We’re trying to invent one. … Can we develop a model that prevents homelessness by intervening in people facing eviction and solve that problem? We have over 300 volunteer lawyers that are helping.

Just to be perfectly clear: We have no idea if this is going to work.

BP: In one sense, this is a national problem. Every city has some version of this. In another sense, it’s a very local problem. Some cities have done much better than others. Houston, for instance, appears to have had great success, San Francisco much more mixed. Is this properly thought of as a national problem or a local problem, or is it the worst of both?

KB: It is a national problem. The difference is the scale. If you look at the states on the West Coast, the numbers are the highest.

New York was ahead of the game. The city policy has a right to housing. And they invested years ago in a system of interim housing. We never did that. In effect, our policy has been: Stay on the street until permanent housing is built.

If you look back on [last] year, probably the biggest change has been the beginning of a system of long-term interim housing. When I started, I thought interim was going to be three to six months. I now accept that interim is probably a year and a half because we are building, but how on earth is it OK to say, “Stay on the street until your number comes up?”

BP: It’s inhumane. It’s immoral, really.

KB: De facto, that was our policy. And that was the policy of the county.

BP: Are you satisfied with your relationship with the county?

KB: Yeah, I think it’s a good relationship. Am I satisfied with all that’s going on? No. But the county isn’t either.

BP: Do you believe that there is a shared sense of not just policy but urgency when it comes to the county, state and federal governments on this issue?

KB: I absolutely believe that, and also that everything needs to be framed by the same goal, which is ending homelessness, not managing it.

The system was not set up, in my opinion, to end homelessness. I do not believe that anybody would have predicted that homelessness would have metastasized to where it is today. … If you are managing homelessness, your contracts and everything you do are not set up with the outcome in mind that people get off the streets permanently.

BP: Is there a reluctance to end homelessness — there are nonprofits and others for whom it is their business — or is this more a conceptual problem?

KB: I will admit to being a little biased on this, as the former executive director of a nonprofit. I do not fault the agencies for this at all. They are not the ones that determine the outcomes. That is the higher authority of the federal, state, county and city [governments] that make certain requirements of them, and that they are abiding by.

All of the public agencies need to set a goal of ending homelessness and need to back it up with the resources that are required. …

What I learned by appointing myself to the LAHSA board [the Los Angeles Homeless Services Authority is a joint city-county agency formed in 1993 to provide services to unhoused people in this region] is that LAHSA awards about 60% of the resources that are needed. It is the expectation of the community program to raise the other 40%.

And you know, Jim, that different agencies have different abilities, resources, access. That’s structural inequity right there.

That’s why I say that the government agencies need to set a goal, but they need to back it up with the resources. Why set these organizations up so that they have to go hustle for 40%? If you are in a more affluent area, you’re going to have better access to donors, better access to other resources, and you’re going to have fewer numbers [of unhoused people].

BP: So you have smaller need and greater resources. And the reverse is true, of course, in poorer neighborhoods, where you have more unhoused people and less access to resources.

KB: Exactly. Where I think we have been deficient is in my old community, the health community. The social service community has, in my opinion, been lacking. Anybody that’s been on the street needs healthcare. Anybody who’s been on the street to the point where their lives have collapsed needs very strong social service support. If you are an agency that is not able to raise millions of dollars, then the support that you provide to your clients is different.

That’s why I believe there need to be uniform standards. The outcome needs to be to end homelessness. And the city, county, state, federal government and private sector, for that matter — whether we’re talking about the philanthropic private sector or the straight, for-profit private sector — everybody needs to weigh in. It is not fair to leave such a massive humanitarian crisis to community-based programs.

BP: How much time do you have to show results? You’re asking a lot of these agencies and of people paying for them. Is there a point where you have to start showing numbers coming down for people to stay with you?

KB: There are a couple of ways to look at it. My measurement that I used in my first year was the reduction of street homelessness. I also had a multifaceted approach to ending homelessness that involved robust interim housing … as well as expediting the building of housing. Those, especially the building, are going to take a while to show results, because even though we’re building faster than ever — or, I should say, we’re permitting faster than ever — it still takes a long time to build. …

My measurement last year was to reduce street homelessness, which we did. …

BP: When you say “reduce street homelessness,” what’s the measure of that?

KB: Encampments.

What I didn’t commit to [in the first year] was reducing the number of people who are unhoused in the city. I didn’t for a variety of reasons. One was that I anticipate homelessness even increasing because of the COVID protections [eviction moratorium] that went away.

BP: Do you feel progress in the area of interim housing, in moving away from the de facto policy, as you called it, of forcing people to live on the street until there is a permanent place for them to live?

KB: Yes. That’s no longer acceptable. … It is unacceptable to have Angelenos on the street. Period. That has to be our viewpoint.

If that is not our viewpoint, then we have conceded. That’s when you are managing the problem, and you are not committed to ending the problem.

BP: I must say, even personally, you adjust yourself to it. You become accustomed to it, and you stop being outraged by it. And it’s outrageous.

KB: It’s absolutely outrageous. And you and I have been around long enough to know that this is not always the way it was, but an entire generation has grown up and seen this their entire life.

BP: Are you learning more about this all the time? Are you discovering new wrinkles to the system that stand in the way of, as you say, peeling the onion?

KB: Yes, I am constantly learning and constantly finding new barriers. … The way this has worked before is that outreach workers would go to the tents. They would talk to you and ask, “Jim, do you want housing?” Yes, you do. “Well, I tell you what, give me your name. And let’s see, where’s your tent located? I’ll be back when I have a spot for you.” If your tent is in the same location six months from now, maybe I have a place for you. But if you move, I have to go looking for you.

So literally, spots would be vacant while they looked for where your tent is.

Maybe it made sense when there were a handful of people who were unhoused. One thing that’s really clear: In the midst of a humanitarian crisis, it’s insanity. …

But what I’m doing is extremely expensive. And by the way, it is way too expensive. It’s several thousand dollars a month, per person, to stay in a motel, $3,000 or more a month to stay in a motel.

BP: Which would pay for the rent in a nice apartment.

KB: Exactly right.

But here’s the thing that Angelenos have to consider: As far as I’m concerned, that’s way too much money. We have to come up with a better model of long-term, interim housing, but in the meantime, it is more expensive to leave people on the street — police calls, fire calls, quality of life, petty crimes around encampments. So Angelenos have to say, yes, this is a crazy amount of money, but give them time to come up with a cheaper model of interim housing.

I would rather spend money keeping people in motels than go back to the old policy of “You stay on the street until we can figure out how to do better.”

BP: Are there new models?

KB: There’s one … called New Beginnings. It’s an improvement on a tiny home. A lot of people describe a tiny home as a tool shed. But these are large enough to have individual bathrooms and a kitchenette. They house two people, sometimes three. …

That’s the model I want to look at. I want to move away from the tiny homes because, again, I’m looking for housing that people could stay in for a year to a year and a half.

BP: Flashing forward a few years. Should we expect a system of shelters that then moves to a New Beginnings-type arrangement — people might spend a year, a year and a half there, and then move to some sort of permanent, affordable housing?

KB: Right. On the shelter side, though, I’m sure there will always be a need for congregate shelters, but that will not be an emphasis. Where congregate shelters really come into play is the emergency situation — a weather event.

But here’s the thing: We are going to have to prepare for summer weather. We’ve only worried about cold weather, but it gets extremely hot now because of climate change.

BP: And in some ways heat is more inescapable than cold weather.

KB: Exactly. And so we’re going to need to plan for weather. And we’re looking at having emergency shelters year-round.

BP: Was deinstitutionalization [the policy of releasing mentally ill patients held without their consent, endorsed by then-Gov. Ronald Reagan and civil libertarians for a combination of bud-getary and human rights reasons] a mistake?

KB. One hundred percent. First of all, deinstitutionalization would have been a great policy if we had followed through. It wasn’t supposed to be releasing people on the streets. It was supposed to have been followed by a model of community-based care, whether it was clinics or housing. That never happened.

But it troubles me when people just focus on that because it misses policies such as welfare reform. When I was back at Community Coalition, we were fighting welfare reform because we knew that women and children were going to become homeless. Before the mid-1990s, there were not women and children unhoused.

BP: I remember you saying it, and other people saying it at the time: “This isn’t welfare reform. This is the abolition of welfare.”

KB: And then there was the debate over the idea of “devolution.” Remember devolution? Devolution was just about dismantling the safety net, but it was packaged as, “The locals know better. We don’t need entitlements. We’ll go to block grants. And we’ll give the power over to the states to decide what to do with the money.”

You can imagine [what would happen] in Southern states that today won’t provide healthcare, won’t accept food stamp money because they don’t want to feed the children they insist on being born.

So we devolved services to the state, the state devolved it to the counties. The city was never fully in that business. …

At the end of the day, we decimated the social safety net. And the problem is when people look at homelessness today, because our culture is so ahistorical, they don’t connect the dots with policies that took place over two decades.

And this is the result of those policies.