Life was rough for Michelle Martinez, a 33-year-old mother of three. She and her family had moved in with her parents, who were paying $800 a month to rent a three-bedroom home in Eagle Rock. Then the landlord died and left the house to new owners, who raised the payments to more than Martinez, her partner or her father and mother could afford.

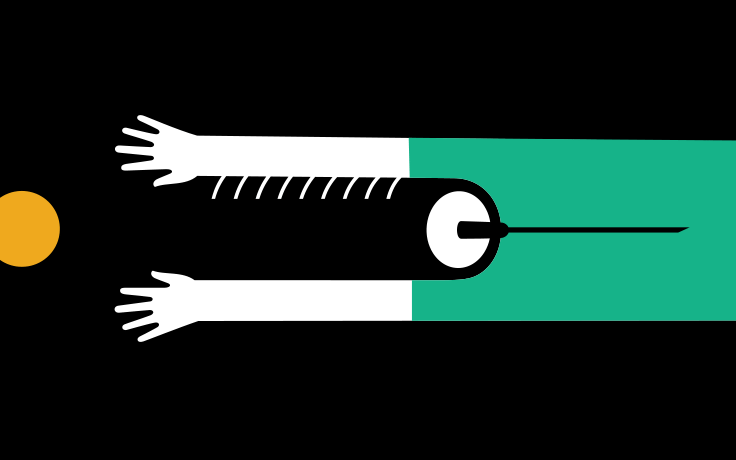

Martinez and her partner had already lost their own home in Commerce because their jobs ended. It wasn’t fancy work, cleaning air conditioning units six days a week, but it had paid enough to live on. Now they were struggling to find something else. Her partner took buses around Los Angeles, where he stood at pick up sites for day laborers along with as many as 40 other men looking for work. In July, Martinez went to the emergency room at LAC+USC Medical Center. She had not been able to eat for five days because her throat was inflamed. She was running a fever, and she could hardly get out of bed. The diagnosis: tonsillitis.

Financial pressures were taking a toll. “It’s probably why my body is breaking down,” Martinez said, sitting in the waiting room at County/USC on a recent afternoon. Long lines snaked toward the door, filled mostly with low-income patients waiting for treatment or prescriptions. “It’s stress-related.”

Linda Rosenstock understands. She is a professor in the UCLA departments of Medicine, Environmental Health Sciences, and Health Policy and Management. Rosenstock knows that health problems for people in Martinez’s financial situation can stem from poverty and income inequality. The social and economic conditions of the poor can even shorten life spans, Rosenstock has found, based upon her assessment of peer-reviewed research. Ill health is the shadow consequence of unequal distribution of wealth, particularly in the United States, which has the greatest income inequality of any democracy in the developed world.

California is near the forefront of this disparity. An analysis of Census Bureau data by the Corporation for Enterprise Development shows that the top 20% of earners in California have an income of at least $124,936 — in contrast to $23,980 for the bottom 20%. That puts this state among the top 10 with the largest gaps between rich and poor.

Lack of resources affects every aspect of wellness throughout a person’s life, from gestation to death, Rosenstock said. The harm goes beyond being deprived of basic health care.

Recession brings new troubles

Rosenstock has been aware of inequities in health and social class since the 1990s, when she served as director of the National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health. “It was clear even back then,” she said, “that workers, for several decades, had been facing added pressures of growing income inequality, with wage stagnation, decreased availability of out-of-pocket expenses [and] decreased resources … for health care premiums. I became fascinated with this as an issue through the lens of workers.”

She realized that lower- and middle-income workers faced pressures that could impact physical and emotional conditions — pressures that upper-income people did not have. Lower-income workers, for example, often endured meager pay; lack of health benefits, such as paid sick leave; and a need to juggle multiple jobs to survive. But it wasn’t until the 2008 recession that most of the country became concerned about these disparities. “Those … issues began to get worse,” she said, “and started to receive more attention from economists, policy makers and politicians.”

Rosenstock and other researchers decided to examine health and income imbalances more closely, an effort that resulted in a recent American Journal of Public Health article, written by Rosenstock and Jessica Williams of the Harvard School of Public Health. Findings showed that lower-ranking civil service employees experienced sharp increases in cardiovascular disease, and that working long hours in general (more than 40 hours a week) under high stress or on irregular shifts contributed to illness. Little control over work life, job insecurity and lack of social support led to increased depression, anxiety, obesity and rates of mortality, including suicide.

The invisible effects of poverty

On another corner of the UCLA campus, Ninez Ponce, associate director of the Center for Health Policy Research, was doing work that supported Rosenstock’s research. Ponce found that income inequality might increase susceptibility to preterm births. By comparing wealthy neighborhoods with areas of economic hardship in Los Angeles, Ponce and her team determined that increased traffic-related air pollution and lack of financial resources corresponded with a greater likelihood of premature births, particularly during harsher winter months.

Ponce, born to Filipino immigrants and long passionate about issues of inequality, recently published a study in the journal Health Affairs, which showed that income disparities also might influence early treatment options for breast cancer. Women in lower socioeconomic areas, she found, were less likely to be screened with a Gene Expression Profiling test, which helps women decide whether they would benefit from chemotherapy. The test costs up to $4,000. The women Ponce studied were insured and did not have to pay for the test, but they still did not get it as often as higher-income women.

“That surprised me,” Ponce said. Was it a provider issue? She is uncertain about the reason. But the disproportion is significant. “Now we have the Affordable Care Act, but having access to care is not going to erase these class disparities,” she said. “It’s important now, because we can’t just feel good and think, ‘Oh, we’ve dealt with un-insurance. Now it’s done.’ ”

Additional recent studies have reinforced Rosenstock’s findings that income inequality affects health. At the University of Wisconsin Population Health Institute, for example, researchers performed “health checkups” in 3,000 counties to rate states on personal care, clinical care, environment, socioeconomic status and mortality. They found that counties with larger numbers of ailing residents also had higher rates of smoking, crime, teen births, physical inactivity, preventable hospitalizations, early deaths and children living in poverty.

Children suffer along with parents

In California, Michelle Martinez was worried that she might have to move again. She also was concerned about her partner. He felt guilty because he could not support the family. He suffered from gallstones. She had Medi-Cal, but he needed $175 in fees under insurance obtained through the Affordable Care Act for his treatment. Despite his condition, he took freelance plumbing jobs. Sometimes he went two weeks without work. Martinez also worried about her sons. All three were anxious. They had panicked when she was admitted to County/USC. Her mother was the only person in the family with a steady job, but she took over caring for the boys while Martinez was hospitalized. One had developed a nasty cough.

Research shows that children, too, can suffer from income-related illnesses. The National Scientific Council on the Developing Child recently issued a report detailing the “toxic stress” that inferior socioeconomic conditions place upon the young and their still-developing neurological systems. Harm, the report said, can come from substandard housing, overcrowded living conditions and exposure to violence, all of which “can have an adverse impact on brain architecture,” impacting regions affected by fear, anxiety and impulsive responses.

Income inequality is no longer an issue that politicians can ignore. A recent Gallup Poll showed that two-thirds of Americans — 75% of Democrats and 54% of Republicans — are dissatisfied with the way income and wealth are distributed in the United States.

“There are vastly different proposals about what to do about it, but it is very clear that both sides of the aisle are realizing they have to talk about the issue, because it’s very much on the public’s mind,” Rosenstock said. Income inequality and its effects on health remind her of climate change 20 years ago.

“It didn’t mean a lot to people personally until we started to talk about how it might affect your health. Then it grabbed more attention, and I think this will be on a parallel course. We’re in that moment now.”