TALK TO PROFESSOR ABEL VALENZUELA JR. about day laborers, and the conversation turns to work as an obligation.

“I would ask myself, what would compel somebody to look for work in public spaces or put themselves in jeopardy of injury to land a job that’s dangerous on the face of it,” he said, sitting in a leather chair during an interview in the UCLA Faculty Center’s billiards room. “All the workers I talked to had a profound connection to this principle: This is what you do. You work.

“You do it to take care of your child, you take care of your family. That would invariably lead to me thinking about the work ethic that many of us are brought up to believe in. When you apply that to immigrant workers, it gives them, if you will, more agency, and it counters the narrative that these men are somehow taking other people’s jobs.”

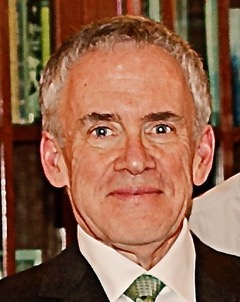

Valenzuela, 53, a warm, engaging man given to khakis, oxford shirts and sports jackets, has been a pioneer in his specialty since the late 1990s. In 2003, he published the first survey of day laborers in Los Angeles, which enhanced his status as an expert in a field that had been untilled in academia.

Now the director of UCLA’s Institute for Research on Labor and Employment, Valenzuela is also co-chair of UCLA Chancellor Gene D. Block’s recently formed Immigration Advisory Council, a panel that will offer recommendations on appropriate responses to the restrictions on immigration put forth by the Trump administration.

There was serendipity to Valenzuela’s focus on day labor. He was just completing his dissertation when he happened upon a newspaper story recounting the concerns of residents in a Northern California community who were upset that scruffy men were hanging around a public park waiting for day work.

“One of my fascinations has always been the world of space,” Valenzuela said. “The geographic context, but also in a broader sociological, political, racial context. How do people inhabit different spaces at work, but also in their search for work? In urban centers, space is really important in terms of the interactions and the exchanges that we have on a day-to-day basis, but also increasingly with regards to work and different types of services.”

Who Are Day Workers?

He decided to survey day laborers. He wanted to understand their lives and the challenges they faced. He was interested in their levels of education and their citizenship status, how they found their work, how they bargained for wages, whether they were always paid, how they were treated on the job and by the surrounding community while they waited for work and if their day labor led to permanent employment.

His survey and subsequent studies in New York and Chicago broke ground in the broader understanding of day labor. It took issue with many long-standing ideas, including that undocumented workers take the jobs of American citizens, especially in the construction trades where many day laborers are employed. Valenzuela has written that this is false because it assumes that job growth in these industries is fixed.

Other research he has done suggests that immigrant workers generally complement workers born in the United States. If there is a negative impact on jobs, it occurs in industries that are already on the decline and heavily populated by minority workers.

Workers gathering in public spaces to find jobs is nothing new. It has a long tradition in this country, as well as in other countries including Japan and South Africa. In the U.S. it dates to the late 1700s, when men, and sometimes women, largely from immigrant populations who had yet to become accepted in the broader society, congregated in town squares to find pick-up employment. In those days, workers found jobs cutting wood, sweeping chimneys and driving carts. Today, day labor is generally focused on construction work, landscaping, painting, woodwork, loading and unloading trucks, and moving household belongings.

Valenzuela’s research shows there are an estimated 22,000 day laborers in the Los Angeles area and 120,000 throughout the United States. An estimated 25% to 36% of them are in the country legally. Forty-two percent have nine years or more of schooling, either in the U.S. or in their countries of origin.

Valenzuela’s surveys have found that their work is sporadic and that their wages vary greatly but are not generally good, placing most day laborers among the working poor. Their work is often dangerous, and safety standards are lax. The idea that day labor is a draw for immigrants to cross the border illegally doesn’t stand up to scrutiny, Valenzuela has written, noting that his research has found that 78% of survey respondents learned about day labor sites only after they arrived in the United States.

“The idea that immigrants would travel thousands of miles, pay thousands of dollars and risk their lives crossing a desert to look for work on street corners is preposterous,” he said.

Lately, Valenzuela has become interested in the vendor economy, which he said doesn’t differ significantly from day labor. “On the most basic level, you can think of day laborers as street vendors. In this context, they’re selling their labor power, their hands.

“In Los Angeles to this day, we continue to struggle about how to regulate space and workers. Day laborers have had to deal with the sort of regulation that mostly bans their search for work, as opposed to regulating their search…. Many of the bans have been overturned as either being unconstitutional or unworkable. If you talk to local law enforcement, they usually become upset [because] they would much rather go after the real criminal as opposed to a worker looking for work in a public space.”

Street vending, Valenzuela said, “has become an important way to earn income in big cities. It shares a very similar spatial configuration [with day labor] that people don’t usually talk about when they talk about day laborers. Space is super important.”

In late January, the Los Angeles City Council moved to decriminalize street vending, but the details may take months to be ironed out.

Son of Migrants to Leading Professor

Valenzuela was born in Boyle Heights. His parents, both from Mexico, were immigrants, his father an upholsterer and his mother a preschool teacher.

Valenzuela said his interest in the kinds of work he wanted to understand came partly from watching his father reupholster and reassemble chairs. “Taking a chair apart isn’t hard. But rebuilding one, that’s a bit more complicated. It might involve breaking the chair down to the basic frame and sometimes reassembling that frame, tightening it up and adding new springs. It required the use of his hands, and he’s very talented.”

From his parents, he learned the value of education and hard work in the classroom. His mother grew up in Ciudad Juarez. As a child, she crossed the border daily to attend elementary school in El Paso until Valenzuela’s grandmother could get documentation for the family to move to the United States. Border crossing for school has been going on for decades, but it might face new challenges from the Trump administration.

Valenzuela earned his bachelor’s degree at UC Berkeley and his master’s in city planning, as well as a Ph.D. in urban and regional studies at MIT. All of his siblings have advanced degrees. A brother teaches political science and Chicano studies at Princeton. One of his two sisters is a public defender in Los Angeles, and the other is a school psychologist, also in Los Angeles. Valenzuela and his wife have three sons. She is an administrator with a health care company that focuses on underserved communities in Southern California.

Valenzuela has been at the Westwood campus since 1994, shortly after completing his Ph.D. He was hired as one of the founding members of the Chicana/Chicano Studies Department and a year later joined UCLA’s Department of Urban Planning as a joint appointment. In addition to his current position, he retains positions in both Chicana/Chicano studies and urban planning.

The Institute and its Mission

The Institute for Research on Labor and Employment is the oldest organized research unit at the University of California. It has two independent research centers, one at UC Berkeley and the other at UCLA, where Valenzuela has been the director since July.

The UCLA center has four primary functions, he said. They are to:

> Train workers in occupational health and safety.

> Provide a human resources roundtable that offers opportunities for executive MBAs and former MBAs who are in government and in the private sector to come back to campus and learn the best practices in human relations.

> Conduct a teaching program that trains undergraduates in labor studies and applied research.

> Operate a labor center, which does policy-driven research.

Valenzuela’s goal for the institute is for it to become much more of a player in driving public policy by working with key stakeholders in Los Angeles and around the state.

“The research has to matter. It has to mean something for California and its residents,” he said. He sees new challenges to that effort in the current atmosphere emanating from Washington.

“The work that we do as social scientists, I think, is going to be increasingly attacked, if the past few months are any indication of how we see future conversations about the value of what we do at this university and at public universities in particular,” Valenzuela said.

“I think doubling down on empiricism, on data and how we collect that data,” is extremely important, he said. “Enhancing it, vetting it, making it accessible, so there’s some transparency — these are some basic sorts of academic processes that I’m re-emphasizing, because I think, in this day and age, that’s being blurred and attacked. “We can’t let that happen.”

Going forward, Valenzuela hopes to study how unemployment and the search for work affect mental health; the demise of public sector unions; temporary work, known as the gig economy; and African-American employment in Los Angeles.

But he always comes back to workers at the lower end of the economic scale, the ones he has placed at the center of his academic focus. He speaks eloquently on their behalf and against the notion that many of them are looking for a handout.

“Many of the workers at the bottom of the occupational hierarchy that I study will often reference their labor with pride,” he said.

“There isn’t a lot of glamour to, say, picking up debris from a construction work site…. When you interview workers about that, they’ll talk about the work. They’ll describe it in detail, and they’ll speak about their job with pride. Though it’s a lousy, lousy job, it’s the entire process of fulfilling the obligation to work, and then getting paid for it, and then being able to feed the family or pay the rent… [that] elevates and makes them a part of the social fabric….

“It’s a way, I think, of integrating immigrants into our American belief system of work.”

Comments