FOR SOME, CLIMATE CHANGE IS A MATTER OF POLITICS, a debate over how seriously to regard the issue, how to exploit it for advantage, how to protect the economy while fully recognizing the gravity of the problem. For others, climate change is an intellectual, or even spiritual, challenge, a reckoning with humanity’s presence on the Earth and its implications for the very chemistry of the atmosphere.

For city planners, however, climate change is a discrete set of specific imperatives. It is about increased heat stroke and more frequent fires. It is about the priorities of hospitals, the difficulties of drought, the effects of sea-level rise, even the dearth of shade. It has moved beyond discussion and debate; action is what is required. And it is happening now.

That’s the case in community after community, in the United States and across the world. Each area faces different tests — snowfall accumulation may be the focus of a rural Canadian outpost, while blinding heat may plague an African city. Caribbean islands brace for wind and storm surge that accompany increasingly strong hurricanes; Central Valley farmers pray for rain or Sierra snowpack.

California cities and towns are squarely at the center of those challenges, because this state is both a leader in responding to climate change and particularly vulnerable to its impacts.

The state’s forests already are suffering, droughts are a recurring plague and, of course, California’s coastline — anchor of its fishing industry, draw for tourists, central to the state’s sense of itself — is being radically altered by the rising sea.

To gauge the enormity of the task confronting California’s local governments, Blueprint concentrated on just one: Long Beach.

Long Beach is a city of 480,000 residents, the fourth-largest coastal city in California. It is home to half of the nation’s largest port complex, which it shares with Los Angeles, and it is both dependent on the oil industry and susceptible to that industry’s impact, globally and close to home.

This Special Report considers Long Beach as a microcosm of the world’s response to climate change, a close look at how one city is attempting to identify and respond to events that are reshaping life on Earth.

Responding in real life

WALKING ALONG THE wooden boardwalk on a narrow peninsula at the eastern end of Long Beach, you can hear the ocean but you can’t see it. A 10-foot to 12-foot high wall of sand completely blocks the view of the beach. The man-made mound built by the city forms the last line of defense between the ocean and a mile-long strip of multimillion-dollar homes. That line is cracking.

Jerry Schubel, president and CEO of the Long Beach Aquarium of the Pacific, sees trouble ahead for low-lying coastal areas like the peninsula, a three-block-wide sand bar that separates Alamitos Bay from the Pacific Ocean. Schubel, who has a Ph.D. in oceanography, is a highly respected expert in the effects of sea-level rise on coastal areas and the marine environment.

Speaking at a climate change event sponsored by the City of Long Beach last January, Schubel was blunt about what the future holds. “Sea level is rising. It is rising at an accelerated pace,” he said. “It will continue to rise throughout the remainder of this century and well beyond, no matter what we do.”

Schubel told the audience that it’s important to distinguish between temporary flooding and permanent inundation of low-lying coastal communities. “Temporary flooding is happening now,” he said. “Permanent inundation is something we can look forward to in a few decades because of sea-level rise.”

A draft Climate Action and Adaptation Plan prepared by the City of Long Beach assumes that sea level will rise by 11 inches in the next 10 years. More alarming are the projections for midcentury and beyond. The city’s climate action plan assumes that sea level will rise two feet by 2050 and as much as 6½ feet by 2100.

Schubel, who serves on a scientific panel that advises California’s Ocean Protection Council, believes those estimates are too low. Based on the latest data, he expects that sea level in Southern California will be 7 feet to 10 feet higher by 2100.

Long Beach architect Jeff Jeannette appeared on the same panel with Schubel. He offered a variety of options for coastal homeowners to consider, including elevating houses and installing storm vents that allow ocean water to flow beneath a structure.

Jeanette acknowledged that those steps, which can be very costly, are only a temporary solution to sea-level rise. “Water will win. We can’t fight it,” he said. “It’s coming. We’re going to get flooded. We need to act as soon as we possibly can to mitigate some of these conditions that are on our horizon.”

Long Beach is considering proposals to restore the natural dunes on the peninsula rather than trucking huge amounts of sand from one end of the city’s shoreline to the other. Other mitigation measures include elevating houses, streets, sewer lines, storm drains and other critical infrastructure. Even all of that may not be enough.

Under a worst-case scenario, the combined effects of an astronomical high tide, a major coastal storm and sea-level rise could flood as much as 9 million square feet of residential and commercial property on the peninsula, in Naples and Belmont Shore. That would cause serious damage to much of the Long Beach shoreline, homes and businesses. There is, of course, another option.

“Over the next few decades, you need to be thinking about moving,” Schubel said. “Over the next 20 years, think about who your least favorite relative is and then try to sell them your house.”

Global damage, vulnerable victims

CLIMATE CHANGE will not spare anyone. It will affect the very rich, those who own the homes that may be flooded or whose yachts may be displaced by rising seas and disrupted marinas. But climate change also will upend life at the Port of Long Beach; those who suffer as a result will be longshoremen and truck drivers, the men and women who load and unload goods. And as temperatures rise, those most stricken by the effects of extreme weather will be the city’s poor and middle class.

As the city’s draft climate plan concludes: “Though climate change will impact the entire City of Long Beach, some communities within Long Beach already experience disproportionate environmental health burdens today.”

Extreme heat events, days over 95 degrees, hit hard in communities that mostly go without air conditioning. The number of those events is growing by the year, with 11 to 16 annual extreme days anticipated by midcentury and 37 a year by 2100. Approximately 275,000 people live in areas of Long Beach that are considered “highly vulnerable” to those heat waves.

Moreover, extremely hot days cause power outages, increase demand for water (at a time when droughts are becoming more common and more severe) and even soften asphalt, a problem in communities with lots of truck traffic, including traffic generated by the port. Long Beach is adding cooling centers for residents to take refuge from the heat, installing water fountains and trying to educate residents on power and water consumption.

Some of those plans are still being developed, but the city will have to spend hundreds of millions of dollars trying to adapt.

Contributor as well as responder

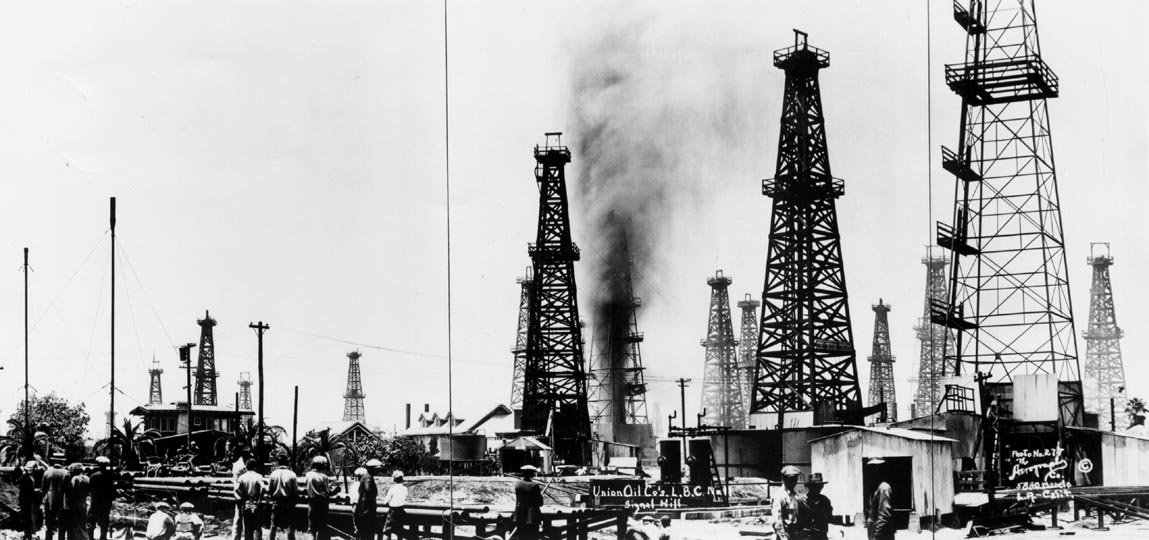

LONG BEACH IS NOT ONLY responding to climate change; it is also grappling with its contribution to the problem. That’s because Long Beach is an oil town.

For decades, crude oil has been pumped 24 hours a day, seven days a week from wells on four cleverly disguised, man-made oil islands built on state tidelands just offshore from downtown.

The city has received more than $450 million from the sale of tidelands oil since drilling began in the 1960s, a drop in the barrel compared to the state of California, which has made more than $4.25 billion from the sale of oil pumped out of the Long Beach tidelands.

From the sand berm on the peninsula, you can clearly see Long Beach’s ties to the fossil fuel economy. There are the four tidelands oil islands. On the horizon, a flotilla of oil tankers waits to unload carbon-rich cargo at the Port of Long Beach.

In fact, crude oil is the largest single import that passes through the port into pipelines that feed nearby refineries. Last year alone, 25.8 million metric tons of crude oil was unloaded from tankers docked at the Port of Long Beach.

That oil is pumped into large pipelines that feed the Los Angeles area refineries that produce gasoline, diesel fuel, jet fuel and bunker fuel. Petroleum coke, what’s left over after crude oil is refined, is the largest single export from the Port of Long Beach. And burning petroleum coke produces more greenhouse gas emissions than coal.

In 2018, 4.1 million metric tons of petroleum coke was exported from Long Beach to 15 foreign countries. More than half of it went to Japan and 22 percent went to China. In 2015, the oil and natural gas pumped from the city’s oil fields produced 8.3 million metric tons of greenhouse gas emissions.

LONG BEACH’S relationship to oil makes it especially difficult for the city to wean itself from dependence even as it attempts to curb greenhouse gases. Long Beach depends on tidelands oil money to maintain its beaches, waterfront parks, shoreline bicycle and pedestrian paths, and to construct beachfront facilities, including a $80 million Olympic-sized swimming pool.

Oil money is even paying for the mitigation of a crisis driven by burning oil. Tideland oil revenues have been used to rebuild sections of the crumbling seawall on Naples Island. During a particularly high tide last summer, water leaked through cracks in the seawall in front of mega-million-dollar homes. More city investment, some of it drawn from oil revenue, will be needed to protect those houses.

How does Long Beach justify contributing to climate change even as it fights to protect itself from its effects? “In the long term,” the city’s climate plan notes, “to maximize carbon emission reductions, the City must explore ways to decrease and eventually phase out local oil and gas extraction.”

In the meantime, Long Beach will build seawalls and cooling centers. It will plant shade trees and bolster sand dunes. Some residents will conclude that it’s not worth the risk. Some of those who can afford to, the richest, will leave. Others will swelter. Some, especially the poorest, will die.