ERIC GARCETTI HAS SERVED as mayor of Los Angeles since 2013, when he defeated Wendy Greuel in a campaign marked by heated disagreements over relatively small issues. Since then, he has presided over some sparkling achievements: He helped secure the 2028 Summer Olympics and presided over the passage of a transportation tax measure that is helping to correct one of the city’s most glaring deficiencies, a subway that bewilderingly fails to connect with the airport. He won accolades for shepherding Los Angeles’ much-admired response to COVID-19 while enduring scorn for two instances in which he was photographed without a mask during the Rams’ postseason appearances this year, an episode he mentions in this interview.

Elected on a pledge to focus on managing Los Angeles, Garcetti’s résumé reflects attention to detail, what he calls “back to basics.” He has, however, occasionally reached for bigger prizes, and with mixed results. Against the advice of many wizened political advisers, Garcetti took on responsibility for housing the region’s homeless and invested billions of dollars in the effort, only to see that population grow. He also inherited historically low levels of crime and fought to keep them that way, not always successfully.

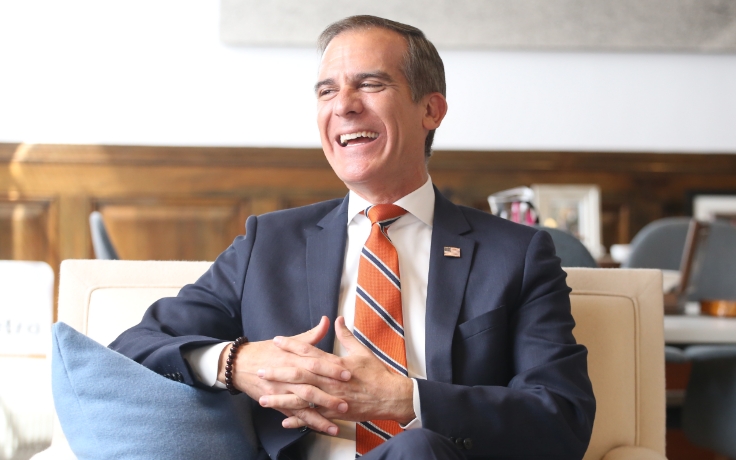

Still, Garcetti has critics but few enemies. Congenial, articulate and gently self-deprecating, he is difficult not to like. Some fault him for failing to wield a heavier hand as a manager or dealmaker; some sense ambition behind his political calculations. But no one questions his intelligence or commitment to Los Angeles.

Garcetti and Blueprint’s editor-in-chief, Jim Newton, met more than 20 years ago at a basketball game hosted by then-Mayor Richard Riordan. Both Garcetti and Newton fouled the mayor during the game (Garcetti still insists that Riordan fouled him first). Garcetti went on to run for City Council in 2001, and Newton has covered his career in the years since. The two met most recently this spring in the mayor’s City Hall office, where this interview took place.

The Garcetti-Newton conversation

BLUEPRINT: I was thinking back to the 2013 race for mayor and wondered if you could reflect on that for a minute. Would you think back to what you heard from voters then about what they wanted from the city and then talk a little about how well you feel you’ve measured up?

ERIC GARCETTI: Well, I’m going to say that I hate … the whole “judge yourself” thing.

BP: Sorry, me too. I mean that less as judging yourself than reflecting on whether those hopes have been fulfilled.

EG: I sure hope so. … I had a little open time today, and I started writing down what I thought, why I wanted to run [in 2013], what I wanted to do and what I remembered having said that I wanted to do. And it was pretty simple. I said I wanted City Hall to work again, and I wanted Angelenos to be working again. Going a little deeper, I wanted to get back to the basics, and the stuff I’d learned as a council member that people care the most about — their block, their park, their street, their call to DWP — that those things get done better.

And then, the second piece — we were coming out of a recession — was to make sure we were building the city of the future by focusing on longer-range economic prosperity for everybody.

So, looking back, on the first [aspect] … I mean, there’s nothing more basic than streets. The year before I got elected, Bill Maher was complaining on his show about L.A. streets. That was a whole segment — his drive to the studio. And I looked at the stats, and there’s actually a rating you get for your streets, from zero to 100, and we had gone down for 30-plus years. Starting with my first year and every year since, we’ve gone up every single year, for the first time ever. You can still find some bad streets, but it’s not the obsession that it was. You don’t hear a lot about it because when you do your job right, you don’t get a lot of praise. Rightfully so, people believe that’s what city government should do.

BP: Nobody writes letters to the editor when they like stories, so I hear you.

EG: Exactly. “Great story! Awesome editorial! Keep going!”

There’s thousands of other examples. Since Riordan said we won’t raise taxes or rates on anything, DWP had been disinvesting in its infrastructure. We’ve more than doubled and tripled the pipes and the poles and just the basic infrastructure. Remember, it was the first year when the pipes burst over near UCLA. … And even housing, where we had 40 years of NIMBYism. The pace has tripled — not like 10% — it’s tripled since I became mayor.

The problem with a lot of these things is if you do it right, it’s not an eight-year fix. It takes decades to get out of 40 or 50 years of not doing it right. …

We built the largest reserve we’ve ever had, really responsible budgets. That first year had zeroes for DWP workers and at one point police officers, which had never been done. Everybody was saying our raises were out of control. Tough stuff to do, but I spent the capital on back-to-basics.

On building the city of the future, the key economics stuff, I also tried to spend my capital there. Measure M [a half-cent sales tax for transportation approved by voters in 2016]; the film tax credit at the state level, which I really pushed through to bring production back; aerospace investment; housing … really trying to envision the future.

We never had a transit line to LAX — it was the biggest applause line of the campaign, even if people had never flown before. And now it’s rising like a Roman aqueduct.

BP: I remember talking with you about this more than 20 years ago. Even then, it was incredible that you could not take a subway to the airport.

EG: It’s insane.

One of the lessons I learned is that some of the small things are much tougher than you ever imagined, but some of the big things are easier than you’d ever think. …

Why didn’t we have that there? Within the first year, we had put together the funding, the plan and the approvals. We still had to engineer it and do it, but that thing’s going to happen. I was like: Wait, did we just do that?

The Olympics took a little bit longer, but those things that I thought were the marquees to rebuild a city [were easier than expected].

BP: As I looked back at 2013, I was really struck at the kind of small-ball issues that dominated much of the coverage — the IBEW endorsement, campaign finance flareups. I felt a little squeamish reading it, frankly, because it feels media-driven.

EG: Never. That’s unbelievable. Not possible.

BP: Yeah, well, we’ll edit that out. … More importantly, though, when you look back, not just at that campaign but at campaigning in this city generally, do the politics seem consistent with the job? Do you end up running on things that matter, or are you forced to run on things that don’t matter?

EG: Well, I make a distinction: There’s the things you run on, and then there’s the things that define the race. So what I run on, absolutely. It’s your only chance to narrate. When you run for office, it’s your only chance to make the promises that then become 80% of what you’re going to do, at least in your first term. … It’s locked in. You’ve said you’re going to do it. You should.

What a race is determined by, though? You never know. Everybody is saying right now that this race is going to be about homelessness and crime. Trust me: You don’t know what this race is going to be about until it’s about what it’s about. That can be very media-driven. It can be about somebody misspeaking. I didn’t think my race was going to be about Water and Power. In fact, I had worked very closely with and done very well with workers there, but because they chose a side, it became a defining issue. I became an outsider even though I had been working here for 12 years.

BP: It was bizarre.

EG: Talk radio was saying: We think they’re both communists, but at least he’s not bought and paid for by the special interests. My reaction was: OK, if that works.

Campaigns are their own beasts. You can try to push the beast in some direction, but usually the beast emerges on its own.

BP: So let me ask you about a couple specific issues. Crime is up. There’s no disputing it. There were about 18,000 to 19,000 violent crimes in Los Angeles in 2012 [the year before Garcetti was elected], and there were about 30,000 last year; homicides similarly up from 296 or so to 397 last year. I’m used to [mayors] running on the strength of bringing down crime, and yet crime’s gone up on your longer watch. Why is that, and what do you have to say about it?

EG: Well, somebody did a data crunch recently that this was the safest decade … that we’ve had in L.A. That takes in a couple years before me, but it’s basically this period.

Couple things: One, we have some more honest numbers [LAPD audits in 2005 and 2009 found serious undercounting of assault data, with thousands of assaults being downgraded to minor incidents], so the increases in violent crime numbers are almost fully attributable to actually counting assaults as assaults and not gaming them as they were gamed before. I’ll take that hit. I’d rather have honest government than sugar-coated government.

The last two years are a particular skew on shootings and homicides. Other than that, we’ve actually had blips up and blips down, but because we’re at such a low number a little blip up registers as a higher percentage. It’s still in a trough.

BP: Well, yeah, if you look back farther: 89,000 violent crimes in 1992. It’s nothing like that.

EG: Those were crazy numbers. …

It was one of the biggest challenges I faced at the beginning, one that we were able to slay. That challenge is there now, and we won’t be there for the two years to see its effect, but I hope that the next mayor will similarly slay this bump up. I remember it happened in 2014, we saw this bump up — a 15% increase in violent crime.

Today, we have nearly a million more patrol hours per year in the police department than when I started. … So we increased patrol hours. … We expanded our GRID work, our gang reduction work, by about 50% of geography covered. … And we’ve concentrated in areas. We had public housing developments that used to have a murder every couple weeks [that] haven’t had a murder in a year.

We’ve focused a lot on moving toward what I call a kind of co-ownership of public safety, [which] I think is about to bear fruit and which has already started to. Amy [Wakeland, the mayor’s wife] was very involved in this. We took DART teams, Domestic Abuse Response Teams, and put them in every police division for the first time. Those are repeat calls and often tragic calls. We have SART teams, Sexual Assault Response Teams, and put them everywhere.

And then three new programs, arguably four: Didi Hirsh Suicide Prevention [Didi Hirsh Mental Health Services is a Los Angeles-based center created in 1942 to provide mental health and suicide prevention services], when you have cops that roll out to someone who’s suicidal and obviously results in a tragedy or they take their lives because they’re triggered or they’re trying to die by cop; cops [alone] don’t know the mental health stuff. Really successful. … Second are our Circle Teams, which are in Hollywood and Venice now, responding to street homeless calls that used to go to 911 [and] are now going to peer counselors and others who walk those streets and know the folks. And then the Mental Health Vans, which began in January and [are] now in two, and soon to be five, parts of the city — 24/7 911 response for the 47,000 calls that LAPD or LAFD gets, and we think we can cover almost all of them [with the vans]. We’re paying for the driver and the real estate, and the county is paying for the clinician and the caseworker. In the first month, just in downtown, it used to be that 80% of those transports were to a hospital, where maybe they get held for three days but usually not and are back on the streets. Instead we are sending 72% into mental health care and only 20% into the hospital. …

But to your larger question: Yeah, nationwide, we’re not an outlier. We’re a little bit lower in some cases. Homicides are up everywhere because people are armed, and we just had a pandemic, when people went stir-crazy.

BP: Homelessness. I remember when you were really setting out to do things on homelessness, thinking, uh oh, because this is hard — practically and politically.

EG: I wish you’d warned me.

BP: It does seem beyond the reasonable reach of almost any elected official, much less a mayor, so the incentive politically is just to avoid it. Obviously, you didn’t take that advice, which I’m sure others offered to you, and that’s to your credit. And yet, it has also, just by the numbers, gotten worse. There’s more of it in Los Angeles today than there was. How do you reflect on that? Was it smart to take on homelessness? Was it essential? Do you worry that you’re now responsible for the increase in homelessness?

EG: I don’t worry that I’m responsible. I think it’s essential. And I don’t care whether it was smart. For me, it’s a core, motivating belief and area of focus of my entire life, and it will remain that way no matter what title I have.

I had a lot of advice — from my transition team, from smart journalists, from others — who said, “Don’t touch this. It’s a political loser. And it’s impossible for mayors.” People don’t understand that the city doesn’t have the causes-in or the cures-out.

BP: Right. I mean, you don’t do social services and you don’t do mental health, so how are you going to fix this?

EG: Exactly. And we don’t have the foster care system or others. We do have some responsibility on zoning and housing, and we can be powerful advocates, and I sought to be the second. Just before the pandemic, I gave a speech where I accepted responsibility for solving homelessness. People didn’t hear the nuance. [They concluded]: “Oh, he’s to blame for homelessness.” No. We’re all to blame for homelessness. Put the mirror up to each and every one of us — each time we said no to housing being built in our neighborhood, allowed a mental health care system to fall apart, didn’t treat veterans or foster youth as we should have…

BP: Or voted for lower taxes …

EG: It’s a collective responsibility. But we need people who run to the fire, and I ran to that fire, and I don’t regret it even if it means sometimes getting burned. Somebody has to put it out. …

I’m proud of what we have in place. Not proud in the sense that we’ve solved homelessness or that the numbers got so great on the streets. Proud in the sense that for the first time, we didn’t have state money for homelessness. We didn’t have a city budget on homelessness. So let’s just take those two. The city budget [on homelessness], if you really wanted to stretch it — it was really zero — but we could call it $10 million. In this year’s budget, it was $1 billion.

I know the next question: “If it’s a billion and it still isn’t working…”

BP: You beat me to it.

EG: I don’t buy that, and I’ll you why… [The state once regarded homelessness as a purely local problem, but now contributes.] Still not high enough, in my opinion, but the state has skin in the game for the first time.

On the federal level, when President Biden asked me to co-chair his campaign, he said: “What do you want?” And I said the only thing I want is that you’ll promise me one thing in your platform, that you’ll look at developing over time, or doing your part to develop over time, a right to housing.

Think about it. We don’t let people starve in America. It doesn’t matter how many of us are hungry. We all get food stamps if we need them. We don’t have people go without health care in America. The poor, the indigent don’t go without it, thanks to Medicaid, which we call Medi-Cal. No limit. …

Every country that’s solved homelessness, and I’ve looked deeply into this, has two things: They have a functioning mental health care system, and they have a right to housing that takes those who are on the streets and offers them housing. Full stop. …

Everything that people asked for — Get a ballot measure? That’s never been done. It will never pass. We did it. Get a second one? Worked on that one at the county level. Got it. We need inclusionary zoning or a linkage fee. We got that passed. Build some shelters? How many do you want? Five? We got 27 of them. … What about tiny home builds? Great. We got 13 and another three coming, including the largest in the country. Safe parking? Not enough of them, but a bunch of safe parking sites.

Whatever you want, I’m never going to be the guy who says we didn’t get it because we didn’t try it. …

I had a teenager follow me around a while ago, and he asked me to boil down to four words where homelessness comes from. I said, Can I have five? Meth, tents, trauma, high rent … Not that everybody who’s on the street is on meth, not that everybody’s in a tent, but in some combination, we have those issues.

Never before did we have groups buying people tents. On one hand, it’s really great; on the other hand, it cocoons people, makes them much more resistant. People did drugs. We had crack, etc., but this meth that’s out there right now is making people psychotic, or they’re using it to treat their psychosis if they had a pre-existing one. Our rents have never been so high. And [then there is] our collective trauma, between sexual abuse and domestic violence, war, the foster care system.

I am truly optimistic. I saw what we were able to do in Venice, in Echo Park, in MacArthur Park, now around here in the Civic Center area. It’s really tough. It’s hand-to-hand. There are a lot of people who have a stake in keeping the status quo on both sides of the spectrum, on the extremes, but I think we’ve cracked the code of how you do it. The question now is: Can you stick with it long enough and build enough housing at the same time, advocate for the mental health care system? …

I’m pretty optimistic that we’ve seen the worst, and it would have been a lot worse without these things. And that’s the last thing I’d say to people who say, “You’re throwing all this money, and still nothing’s happened?” Trust me: If we didn’t have these things, it would have been that much worse. I don’t care whether this was the good thing to do politically. It’s the right thing to do.

BP: Correct me if I’m wrong, but I’m going to assume that the biggest surprise of your tenure was COVID. I certainly didn’t see that coming…

EG: Oh, no, I predicted that: “We’re probably going to get a pandemic. Probably from Wuhan.” No one knew what I was talking about, but I kept saying, “Wuhan, trust me. It’s going to be a big deal.”

BP: Well, huge marks for you personally and for the city early on. You were among the first to recognize and respond to this, but you also faced some difficulty emerging from it, and I won’t belabor your issue with not wearing the mask during the NFL playoffs….

EG: Ugh. I’ll shoot myself in the head.

BP: Obviously, COVID was a huge crisis that you didn’t have any reason to brace for. Looking back on it, did it go as well as it could have, better than it could have? What’s your appraisal?

EG: Judging a pandemic is like judging a war, except that you don’t have a final declaration. But I’m so proud of Los Angeles. I’m so proud of the city. I’m so proud of the actions that we collectively took. There are probably tens of thousands of people who are alive today who wouldn’t have been. Tens of thousands. That’s a life well-lived if we did nothing else collectively.

We’ll never be able to count the living. We can only count the dead. But we were the first city to close things down. We were the first city to mandate masks. We were the first city to test people without [symptoms]. We were the first city to go into our skilled nursing facilities. We were the first city to take the African-American deaths that were double the population in other places and bring them under the represented population. It showed the very best of L.A.

I’ve always said that leadership is defined not by the things you say you are going to do and set out to do and how well you do them. Leadership is defined by what you don’t expect to happen and how well you respond. By that measure, I’m proud of what we did here. …

It was unlike anything we’ve experienced in our lifetimes. And mobilizing $75 million in donations before the federal government was there, making the pitch to the Trump White House and successfully getting cities added to the coronavirus relief funds. … We spent all our reserves and maxed out all of our credit cards, and we had no idea where tomorrow we would get the next dollar.

It was the most profound leadership lesson I’ve ever had. I call them the four “ates”: accelerate, collaborate, innovate, communicate. On that last piece, I read somewhere. … that the chief responsibility of a leader is to communicate relentlessly in a crisis. That’s why I started doing those evening addresses.

It was superb working with this governor, superb working with my fellow mayors.

BP: Looking ahead over the next five to 10 years, what do you see as the major challenges facing not just Los Angeles but all of California? How do you govern this place going forward?

EG: California has really one fundamental challenge, which is: How do we get out of the way to be a more frictionless government and economy? How do we take all our well-intentioned laws that have piled up like a bag of stones, each one beautiful but way too heavy to carry anymore, and build more housing and infrastructure?

The top three issues for both city and state? They are housing, then housing and then housing. There’s the American Dream, and then there’s the California Dream. It’s not to say that people don’t dream in other states, but you never hear the phrase “the Kansas Dream,” “the Texas Dream,” “the Florida Dream.” Californians, Americans and even people around the world have always known what the California Dream was. It was great weather, it was awesome jobs, it was good education and abundant housing.

We still have great weather. We still have great jobs. Higher education is still very good, though we have our K-12 challenges. … But that last one, housing, it’s killing the idea of the California Dream. I think CEQA [the California Environmental Quality Act, which permits lawsuits to block construction on environmental grounds] is a part of that.

BP: This is a special test for Democrats, right?

EG: It can only be led by us. We Democrats, who control the state, have to be the ones who push back on ourselves. Individual needs can’t outweigh the collective need to make sure this state doesn’t strangle itself.

And it isn’t good enough to say we’re outpacing Texas, which is true, or that L.A. is leading every city in America on job growth [also true]. We’re No. 1, double the pace of California and better than every city, including all the Texas cities, New York and Chicago, on job growth out of the pandemic, and in the valuation of our companies.

But how much more could we be doing? And if you have any honest conversation with anyone who’s planning their life here, unless they’re already super-rich or too poor to move, people are thinking [about options].

BP: And you can’t tell people that they’re well off, right? They either feel it or they don’t.

EG: We’re rich in all sorts of things that other people don’t have. In the weather, in the geography, in the events that are here, in the sports championships…

BP: I’m a Giants fan. Don’t get me started.

EG: Oh, I’ll get you started. [Garcetti goes to his shelf and pulls down a heavy piece of cable, mounted on a stand.] This is a piece of the Golden Gate Bridge. It’s what I won when we beat the Giants. See, it says “GGB.” One of my proudest wins.

So, we’re rich with those sorts of things, but you’re right, it’s a tougher city and state to live in than it’s been in a long time. It’s not that it’s not better than other places. It still is. It’s this imperfect paradise, but our imperfections are much more keenly felt. …

This is a liberal city in a liberal state, but we’ve mostly been libertarian. Build me freeways and get me water, and we’ll take care of the rest.

BP: And that’s what makes this a hard problem for Democrats, right? There’s nobody else to blame if this doesn’t work.

EG: Absolutely. And I think we’ll remain. I don’t think we’re going to lose power. It’s just a question of what do you want to look back on. Did you retain power? Or did you make life better?

Photographs by Iris Schneider