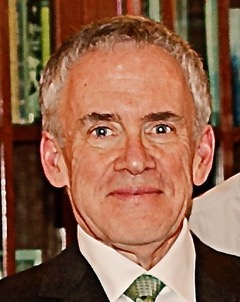

UCLA economist Lee E. Ohanian does not regard income inequality as the critical problem of our time.

Though he acknowledges its effects on society, he sees it as a distraction from the greater public policy issues surrounding the nation’s overall economic well-being.

Not that he’s immune to the hardships of people on the lower rungs of the economic ladder. “There is no doubt that the poorest Americans struggle mightily, and that too many Americans are poor,” he has written.

He’s heard the arguments from populist economists that the American economic system is fundamentally unfair. But he has also noted that these critics have not provided any good criteria for determining economic fairness or unfairness, and has bluntly argued what some seem afraid to acknowledge outright: “There is always some inequality in any vibrant economy.”

Ohanian, a professor of economics and director of UCLA’s Ettinger Family Program in Macroeconomic Research, is interested in more fundamental issues that he believes should be the basis of the public policy debate. His focus is the vitality of the overall economy. To that end, he sees the question of “equality of opportunity,” which gives workers on every rung of the economic ladder a chance to succeed, as the bigger concern.

He’s alarmed by the 35% decline of entrepreneurship in the U.S. since the 1980s — most of that, he said, coming since 2009. When entrepreneurship drops, job creation drops, dragging economic growth with it. He looks at the slowing growth in productivity — which over the last few years is below its historical average — and sees potential problems in job creation and investments in technology.

That leads Ohanian to a very different emphasis than that of some of his counterparts. “Americans,” he wrote in the August / September 2012 issue of the Hoover Institution’s Policy Review, “should care about the well-being of the nation as a whole rather than whether some people earn more than others.”

As that suggests, inequality per se does not especially bother Ohanian: Indeed, he said he wouldn’t mind seeing income inequality double if it meant there was more entrepreneurship and that those on the lower rungs of the economic ladder were doubling their incomes.

Ohanian, who is also a senior fellow at the Hoover Institution at Stanford University and an adviser to the Federal Reserve Bank of Minneapolis, has continued to probe questions of growth and equality in an updated version of his 2000 paper, published in the journal Econometrica, “Capital-Skill Complementarity and Inequality: A Macroeconomic Analysis.”

In the introduction to that research, Ohanian and his co-authors wrote that “the relative quantity of skilled labor has increased substantially [in the postwar period], and the skill premium, which is the wage of skilled labor relative to that of unskilled labor, has grown significantly since 1980.”

Drawing on 35 years of data, Ohanian methodically points to the causes and conditions that he argues have led us to where we are today.

Measuring inequality

One of the starting points for Ohanian’s analysis is to note that there is no agreement on the terms of the debate itself. When it comes to inequality, he said, “There is no systematic gauge or measure, and statistics differ by how it’s measured.”

Some studies, for example, look at household income, others at individual income. Some that focus on the poor include only cash income and don’t include the value of financial assistance from non-cash transfer payments — benefits supplied through Medicare, Social Security or other similar assistance programs. At the other end of the spectrum, some studies of income disparity fail to account for capital gains or retirement benefits or health insurance, all of which often benefit wealthier Americans more significantly than the poor. The variety of measures, he said, “makes it hard for the layperson to get a sense of what [income inequality] is and how it has changed” in the last 50 years.

He also contends that there is no real evidence that income inequality is a threat to the overall economy. He cites countries — Pakistan, Spain, Italy and, of course, Greece — that have more income equality than the United States but far more serious economic problems.

By turning the discussion from inequality to growth, Ohanian identifies a different set of issues that he argues should be on the public policy table: how to keep up with the changing role of technology in the world; foreign competition and the role of American workers in the global marketplace; and the failure of the U.S. education system to prepare students to be competitive with their counterparts in other countries.

Technology, he said, is the primary reason for the increasing income gap in the United States. For several decades after World War II, he said, technology was the great leveler in American society, providing good jobs for American workers. In the 20th century, American income inequality reached its low point in the 1950s, when techno¬logical change was rapid and standards of living increased dramatically.

But sometime around the late 1970s, technology’s economic impact began to change. It went from being an equalizer to a factor that became “complementary to people who were highly trained [and] highly skilled.” And, in that transition, less-skilled workers were left behind.

Ohanian cited, for example, longshoremen working in the ports of New York and New Jersey. About 50 years ago, he said, there were several thousand workers and they handled about 20% of the cargo those ports handle today. This was basically manual labor, not highly skilled, and was practiced by a lot of brawny guys wearing knit caps. They were highly unionized and made middle-class incomes.

Now the number of longshoremen working in those ports has dropped to a few hundred and, for the most part, the workers are college educated with high computer skills, which they use to program and operate computer-controlled cranes that move vast cargos on and off ships.

At the same time, whole industries such as the textile business have largely disappeared from the American scene because it is cheaper to do business overseas. Much of the production is now coming out of Thailand, Vietnam or Mexico, where companies can find a cheaper workforce.

And though raising the minimum wage, as the city and county of Los Angeles are in the process of doing, may seem like a good idea for helping the poor, Ohanian questions its viability as economic policy. Pointing to the once-vibrant textile industry as a case study, he argued that companies will find ways around these mandated pay raises for their less-skilled workers.

“We want all people to be worth $15 an hour, but not everyone has that value,” he said. “How long will it take McDonald’s to develop an Uber-style app that allows customers to do their own ordering?” And once it does, will McDonald’s still need to staff its counters with $15-an-hour workers?

The importance of education

Ohanian was raised in Los Angeles. He attended public schools here before going on to UC Santa Barbara for his bachelor’s degree and the University of Rochester in New York for his master’s and Ph.D. He grew up with the same assumption shared by many of his generation: What a worker earned at the age of 25 could be doubled by the time he or she reached 50. That is no longer true. Without a college degree, the factor of income growth for a modern American worker from 25 to 50 is perhaps 1.3 instead of 2, he said.

Ohanian blamed much of the change on the K-12 education system, which is just not responsive to the realities of what American children need in order to be competitive in the world. For nearly a generation, math and science test scores have dropped dramatically in the United States. The Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development’s Programme for International Student Assessment test released in 2012 — which focused on mathematics with reading, science and problem-solving minor areas of assessment — ranked the United States in 36th place, well below Vietnam, Iceland and Slovenia in test scores.

Only one state in the nation, Massachusetts, seems to be doing an adequate job teaching children math and science, Ohanian said. But it is still two years behind Shanghai, which was at the top of the PISA test, he noted. Fixing the educational system would, he’s written, “do more to reduce income inequality and increase prosperity than any other public policy fix.”

And if these educational problems aren’t fixed so that American workers can be more competitive, Ohanian wonders if we may face a time when there is a permanent underclass in this country: We “have to give low earners a message of hope.”

What is “fairness”?

To those who see the system as rigged, depriving the poor of any real hope; to those who contend that fairness demands redistribution — higher taxes on the rich, more support for the poor — Ohanian has a warning: “Fair share is in the eye of the beholder.”

It is tempting to make a Bill Gates or an Eli Broad commit more of his wealth or income to taxes. But, as Ohanian points out, their entrepreneurship in starting new industries or transforming old ones has created tens of millions of jobs, while their philanthropic work, at home and abroad, has enriched culture, promoted scientific research and raised standards of living. Taxing them more heavily would not necessarily produce a better life for those their efforts have assisted.

And when he thinks about higher taxes and a less competitive workforce, Ohanian cites the example of Greece. For years, Greece has been the recipient of billions of dollars in capital loans, but lenders supplied that money with little over¬sight. Much of this influx of funding, which could have gone to encouraging entrepreneurship, fixing infrastructure, developing business and retraining the workforce, was merely consumed or directed to pensions with little thought for the country’s future. Greece, an ancient center of shipbuilding, now is mainly reliant on tourism. And how much growth can it expect there?

For Ohanian, the contrasting model is Ireland, which has had its own economic struggles over the past decade. But Ireland, he argues, has been able to draw new industries, including pharmaceutical companies, “on the basis of having favorable tax laws and a highly trained workforce.”

There are fewer working people in Europe today than there were in 1955. The hours worked by adult Europeans overall have declined 35% since the 1950s, Ohanian’s research has concluded. In those days, entrepreneurship was encouraged, and growth was steady. It started to decline, he argues, as rising taxes and government regulation made Europe a less hospitable place to do business. That led to a stifling of entrepreneurship and a loss of jobs.

“The first dictum of taxation is ‘Don’t kill the golden goose,’ and Europe did that,” he said. The result: “Europe has had no successful startups in the last 30 years,” he said — at least no startups that could be compared with the likes of Amazon, Microsoft, Oracle or Starbucks.

All of which brings Ohanian back to his central point: A healthy economic model encourages entrepreneurship, even if that means tolerating a certain amount of inequality. The United States should encourage immigration by making it attractive for smart young people to come to this country and stay. And it should resist the temptation to punish the rich. Instead, the goal should be to lift all boats, even if yachts are lifted faster than dinghies.

“Get 1,000 startups going and if you’re lucky, one of them will be the next Microsoft,” he said. “But you have to throw a lot of seeds and hope they sprout.”