IF THERE IS ONE THING all Angelenos have in common, it is that they spend too much time stuck in traffic, moving at the proverbial snail’s pace on exhaust-filled freeways and roads. Congestion, whether on the commute to work, to an evening at Dodger Stadium or elsewhere, has become a quintessential Los Angeles cliché and a frustrating truth.

Gritting teeth over gridlock goes back further than many realize. That is revealed in a UCLA Luskin Center report published in September 2020. The 53-page “A Century of Fighting Traffic Congestion in Los Angeles, 1920-2020” reveals that efforts to ease congestion date to when automobiles competed for space on a young city’s roads with horse- drawn carts, bicycles, pedestrians and early mass-transit options. In 1920, city leaders, frustrated by streetcars falling behind schedule, enacted a daytime downtown parking ban. “Irate motorists soon staged a revolt against the ban,” the report states. “In a mass act of civil disobedience, a caravan of drivers came downtown and blocked the streets.” The ban was quickly lifted.

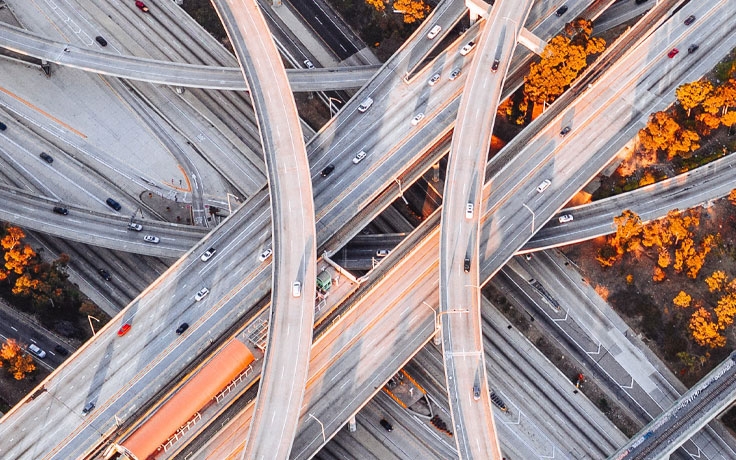

This was just one in a litany of attempts over the years to speed up traffic flow. The Luskin report, by Dr. Martin Wachs, along with Peter Sebastian Chesney and Yu Hong Hwang, shows that local leaders have employed tactics ranging from tweaking land-use planning and zoning regulations, to using new technology, to building roads and freeways crisscrossing the county — which, notably, are now jammed.

Most endeavors to ease traffic jams have largely failed to bring lasting change. Often-expensive construction projects temporarily eased congestion, only for traffic to thicken again as commuters clogged the new lanes, a syndrome known as “induced demand.”

“Building a bunch of extra freeways in the 1940s and ‘50s didn’t fix the problem,” said Chesney, who recently completed his Ph.D. in history at UCLA and is now working as a consultant. “There are still voices saying, ‘Let’s build double-decker freeways everywhere in Los Angeles.’ That would be a tremendous boondoggle, instant waste, and would also be terrible for freeway-adjacent communities.”

Chesney joined the project at the invitation of Wachs, a legendary figure whose career included chairing the UCLA Department of Urban Planning for 11 years (he died in April at age 79). The report includes an eye-opening timeline detailing scores of attempts to hasten vehicular flow. While showing what hasn’t worked in the past, the authors also make the case for trying something new in the future: congestion pricing.

Are roads free? Should they be?

The proposal is controversial, primarily because it suggests charging for something — access to public roads — that millions now use for free. It raises questions about equitable application, with concerns that affluent drivers will welcome tolls to avoid traffic and leave lower-income Angelenos inhaling their exhaust.

Congestion pricing has been instituted in cities including London, Stockholm, Singapore and Milan. Analyses have found that traffic decreases and there is greater use of alternative forms of travel. Congestion pricing also generates significant revenue.

Elements differ depending on location. A 2019 report by the Southern California Association of Governments notes that a plan initiated in London in 2003 charges approximately $15 to drivers who pass a “cordon” to enter the central business district during work hours on weekdays. In Stockholm, rates to enter the heart of the city vary depending on the time, maxing out at about $4.25 during rush hour.

Chesney sees this as an opportunity for Los Angeles to make a change. “If you want to have the privilege to make it predictably from point A to point B,” he said, “that’s something you should be willing to pay for.”

He is not the only one who glimpses the potential. SCAG’s 156-page “Mobility Go Zone & Pricing Feasibility Study” explores the impacts of a comprehensive traffic-reduction program west of the 405 freeway in Los Angeles, extending into Santa Monica. It envisions incorporating congestion pricing, express commuter buses, bike sharing and more, in an effort to persuade people to try anything but driving solo into a busy area. The report cites SCAG’s “100 Hours” campaign, named for its estimate of the time Angelenos lose in traffic each year.

Modeling, according to SCAG, shows that the Mobility Go Zone would reduce vehicle miles traveled by 21% during peak intervals, and vehicle hours traveled in the area would fall 24% during peak times (some trips would shift to less busy periods).

If congestion pricing were attempted in Los Angeles, Metro would play a lead role. The transit agency is deep into what is known as its Traffic Reduction Study. Earlier this year, Metro listed four areas where a congestion pricing pilot program (one independent from the SCAG effort) could be tried, including downtown, the Santa Monica Mountains Corridor and the 10 freeway west of downtown. Joshua Schank, Metro’s chief innovation officer, said the study grew out of the agency’s Vision 2028 Plan, which seeks not only to boost the use of public transportation but to explore other means of reducing traffic and improving mobility.

Schank said congestion pricing is being discussed in other U.S. cities, including New York, Seattle and San Francisco. The successes in London and Stockholm in particular, he believes, could be models for Los Angeles. But any plan will require clearing public relations hurdles.

“You see resistance to congestion pricing in every city, but once it’s in there, it tends to be popular, and that is because it works. You see pretty substantial and dramatic traffic reductions,” Schank said. “You also see greater availability of funds and greater usage of alternative modes. In London, we see a lot more biking and walking than we used to since congestion pricing. You see a lot more bus usage as well.”

Metro has a long lead time. It plans to initiate a pilot program in 2025. Tham Nguyen, project manager for the Traffic Reduction Study, said a technical analysis is currently underway, and extensive community outreach will take place. Predicting pricing is premature. Nguyen said the cost will be determined through modeling, surveys and other tools that result in a full financial plan.

The challenge of equity

If congestion pricing is part of L.A.’s future, the issue of equity will be front and center, with a need to ensure that a program benefits more than people with wallets fat enough to afford tolls. Chesney said a system that results in fewer drivers would speed up travel for the myriad Angelenos who ride public buses.

“The equity question is how to make it so buses work,” he said, “so people who can only afford to navigate the city that way can do so.”

Schank urges taking a more critical view of the present.

“We often forget how inequitable the current system is,” he said. “We think, if we price the roads, that would be unfair to people. But how is the current system unfair to people? For one thing, the 1.2 million transit riders, most of whom are on buses, are on buses that are stuck in traffic, and they’re stuck in traffic that is full of single-occupancy cars. So I would ask, ‘Why are we allowing that to happen?’”

There are other components to addressing equity, including how tolls are used. The SCAG report says that revenues in Stockholm paid for a commuter-train tunnel under the city, as well as new train lines. Chesney suggests congestion fees could provide free bus service in heavily impacted communities.

Fewer vehicles on the road also would improve air quality. Pollution disproportionately impacts lower-income communities alongside traffic-clogged corridors. Chesney and Schank cite higher rates of asthma and other impairments for people living in these neighborhoods.

Although a world of new tolls represents a leap into the future, congestion pricing advocates say that local baby steps have already been taken. The 10 and 110 Freeways have carpool express lanes that solo drivers with FasTrak transponders can choose to access for a fee (the rate varies depending on time of day). A similar lane operates on 18 miles of the 91 Freeway between Orange and Riverside counties. All have been lauded as successful.

Initiating a wider system — perhaps charging people to drive into downtown L.A. — would require public champions. Chesney thinks that coming out of the pandemic, before workers return en masse to office towers, presents a unique opportunity for such advocates. “It’s a sensible time to be thinking about traffic congestion,” he said.

The Metro team takes it further, building on the UCLA Luskin study by pointing out that everything tried in the past few decades has yet to materially change the status quo.

“We’ve picked all the low-hanging fruit,” Nguyen said. “We have to explore more challenging, bolder strategies if we want to achieve our goals.”

No one pretends congestion pricing alone will eradicate gridlock. Rather, it is viewed as only a single tool in a larger kit addressing one of Southern California’s most persistent problems. Schank likens the overall issue to supply and demand: Metro is responding to supply with a swath of projects across the region, from major infrastructure developments to micro-transit efforts. Congestion pricing is a means to reduce demand on the goods — the roads — that now cost nothing.

“You have to do both. You can’t just do one without the other,” he said. “We’re definitely doing a lot on the supply side. Through the Traffic Reduction Study, we plan to do more on the demand side.”