AT THE THREE-DAY CHILDREN’S CAMP HE SPONSORS AT HANSEN DAM PARK, Los Angeles City Council president Herb Wesson is known by the kids as Chief. One summer day, I saw Chief solve a big problem. A boy wanted to skip the session on kayaks and go swimming instead. No, his counselors said, he had to stick with the program — kayaks first, then swimming.

Chief mixed humor with firmness, and soon the boy was laughing and heading toward the kayaks. It was another quiet victory for a man whose mastery of politics, power and behind-the-scenes maneuvering has made him — at least in my mind — the Not So Secret Boss of Los Angeles, or at least of that patch of intrigue known as City Hall. He’s no secret among the city hall crowd, which knows and obeys him. But outside of Civic Center and his district, Wesson is all but anonymous.

In theory, the most powerful person in City Hall is Eric Garcetti, mayor of Los Angeles and its 4 million people. He runs day-to-day operations and shapes long-range policy through his annual budget. And he has a big staff dedicated to implementing his plans and making him famous enough to run for higher office, such as governor or U.S. senator.

But if you want to build a 32-floor high-rise in Hollywood, approve a $100 million bond issue for the homeless or encourage the Department of Water and Power to increase its use of recycled water, see Wesson, the first African American city council president. He heads the 15-member body, which writes the laws implemented by the mayor and votes on the mayor’s appointments to city commissions. Among them are commissions that set policy for such crucial tasks as policing the city, running the airport and, of great importance in this time of drought, delivering water and power to Los Angeles residents. As president of the council, elected by his colleagues, Wesson appoints the chairs of council committees, where ordinances are prepared. He also appoints the committee members, deciding whether a colleague gets a committee with “ juice” — the ability to attract campaign contributors — or is doomed to obscurity on a committee with little influence.

Growing up in politics

He does all this with political skills learned from the ground up, on the streets of South Los Angeles’ African American neighborhoods. He finished his education with a master’s course as speaker of the state Assembly, where California politics were once shaped by two legendary Assembly speakers, Jesse Unruh and Willie Brown.

But these details don’t completely explain why Wesson is the boss, just as they didn’t with Unruh and Brown. “It’s all about your personal relationships,” Wesson told me. Like Unruh and Brown, Wesson understands that a political boss must dig deep into the psyches of colleagues and followers and know their desires, weaknesses and strengths. The boss must be willing to punish, as Wesson did by dumping two committee chairs who opposed him — Jan Perry and Bernard Parks. But the boss also must be generous, giving colleagues full credit for accomplishments. That’s why it’s best for Wesson to stay behind the scenes instead of basking in the spotlight.

Bill collector, comic, politician

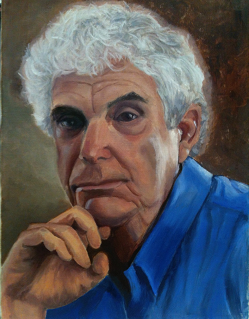

Herb Wesson Jr. stands 5-feet-5, a man of 64, who wears nicely designed, expensive-looking suits, or stylish sport clothes, depending on the occasion. He grew up in Cleveland, Ohio, son of a union auto worker. He dropped out of Lincoln University, a historically black school in Pennsylvania, to come to California and try for a career in politics. Later, he returned to graduate.

In July, we talked about his life and work, first in an interview at his field office, located in the heart of the 10th District, which extends from Koreatown to Baldwin Hills. Then I visited Camp Wesson, the experience he puts together every summer for South Los Angeles youngsters. I watched Chief hang out with the kids as they played, supervised by counselors.

He told me how chance brought him his first political job.

He had met Rep. Ron Dellums, a dynamic, liberal African American congressman from Berkeley, and heard him speak. “I remember turning around to my fraternity brother and saying, ‘That’s what I want to be. I want to be him.’”

It took a while. First he was a bill collector in Los Angeles. He was a standup comic. “I think I got paid for one or two jobs, something like 100 bucks.” He also sold waterless cookware. “I would go downtown and approach women and say, ‘Can I give you a gift?’ If someone would take a gift, I would sell them on inviting me to their house, and they would invite people, like a Tupperware party.”

How well did he do?

“Let me put it this way,” he said. “In 45 days, I bought a Cadillac.”

An acquaintance told him that Rep. Julian Dixon, an influential African American congressman, was looking for volunteers. Wesson made a wrong turn driving to Dixon’s office and ended up at the headquarters of Nate Holden, who eventually was elected to the City Council. That’s how I first met Wesson. The tempestuous Holden had been accused of accepting a shady campaign contribution. I went to his office to ask him about it. Holden was seated at his desk. Wesson, by then his top aide, stood nearby. Instead of replying, Holden exploded into huge, wrenching sobs. “Chief, chief, can I help you?” Wesson said, fetching a wet paper towel.

As it turned out, Wesson was more than a towel holder.

“Nate gave me a shot when nobody else would, and I did my very best to take advantage of it,” Wesson said. “I would work seven days a week.” After Holden, Wesson joined the staff of County Supervisor Yvonne Burke. “Yvonne smoothed my edges and really taught me how to control my ego and that the important thing wasn’t getting credit,” Wesson said. “The important thing was getting the job done.” From there, he was elected to the state Assembly, where members were limited to three two-year terms. He rose to speaker, and then returned to Los Angeles when his term expired.

By then he was a power in South L.A. politics. With support from unions, Los Angeles businesses and Sacramento friends, he was easily elected to the City Council.

As he rose to power and learned his way around City Hall, Wesson and his wife purchased a home in Mid-City and a rental property in Ladera Heights. In the process, David Zahnhiser wrote in the Los Angeles Times, he found himself struggling “with a considerably more mundane set of issues: paying the bills on time.” Zahniser and Daniel Guss on the website City Watch revealed that Wesson had several default notices saying he and his wife were months behind on their mortgage payments. Wesson said he has caught up on his payments and “we have been working with a financial adviser to get our household finances back on track.”

Handling the council

The stories of two council members — Marqueece Harris-Dawson and David Ryu — show how Wesson wields his power.

Harris-Dawson was an accomplished young African American leader who headed the Community Coalition, which has long fought for improving schools and against the neglect blighting South L.A. With a seat open in the 8th District, Wesson met with Harris-Dawson, heard his campaign plan and decided to back him. “When I come in, I come in big,” Wesson told Harris-Dawson. He suggested contributors and met with him weekly to advise him on his campaign. He told Harris-Dawson that he was one of the “next generation of African American” leaders, “so I am going to take the time to walk you through” the campaign.

After Harris-Dawson won, he asked for a seat on Transportation, a juice committee that affects construction and engineering firms and other potential contributors. “Just couldn’t give it to you,” Wesson told the rookie. Instead, as council president, Wesson made him co-chair of a new committee on homelessness and poverty and told him it was important for a progressive African American to do that job, given the fact that a substantial number of the homeless are black. It turned out well for Harris-Dawson. The committee, at the center of trying to solve L.A.’s homeless crisis, has gained him significant attention.

Ryu was elected to the council over Wesson’s opposition. He had been a leader of Korean Americans fighting Wesson’s reapportionment plan, which divided Koreatown among council districts and gave Wesson a substantial portion of the area — with its many nightclubs, restaurants and other businesses that are big sources of campaign contributions.

But despite Ryu’s opposition, Wesson welcomed him to the council and helped him navigate through the city bureaucracy. “He wants to be able to deliver services for his district,” Wesson told me, as we ate lunch at a Hansen Dam Park picnic table. “I spend my time making peace. I hold no grudges. None.”

Not everyone is enamored of Wesson’s methods. “I think he can be charming. I think he is very slick and is not honest because when the man wants something done, he gets it done,” said attorney and Koreatown leader Grace Woo, who ran against Wesson and opposed him in the redistricting fight. “He knows how to count his votes, as he likes to say.”

Wesson, the vote counter, knows it takes just eight of the 15 councilmembers to dump him from his job. That would put the brakes on a career that could include a run for county supervisor or mayor. Ambition brought him to his present heights from bill collecting and selling pots and pans. As he looks around the council chamber from his perch on the rostrum, he knows the same sort of ambition burns in some of his colleagues. And as he and the others realize, in City Hall a friendly backslap can quickly turn into a stab in the back.